Phylogenetic Inference

Phylogenetics is the study of the evolutionary history andrelationships among individuals, groups of organisms (e.g.,populations, species, or higher taxa), or other biological entitieswith evolutionary histories (e.g., genes, biochemicals, ordevelopmental mechanisms).Phylogenetic inference is the taskof inferring this history, and as with other problems of inference,there are interesting and difficult questions regarding how theseinferences are justified.

In this entry, we examine what phylogenetic inference is and how itworks. In the first section, we briefly introduce the field ofphylogenetics and its history. In section 2, we explore howphylogenetic inference provides useful problems for philosophers toexamine, and where philosophical approaches have contributed to thescientific examination of phylogenetics. This will help display whyphylogenetic inference is not merely a biological research problem,but a philosophical one as well. Finally in section 3, we will move toa discussion of some of the contemporary debates about foundationalissues in phylogenetics, and what the future of phylogenetic inferencelooks like.

- 1. Phylogenetic Inference in Biology

- 2. Phylogenetic Inference and Philosophy

- 3. Looking Ahead: New Challenges and Opportunities

- Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Other Internet Resources

- Related Entries

1. Phylogenetic Inference in Biology

1.1 Primer and Introduction to Phylogenetics

A phylogeny is a reconstruction of evolutionary history. Thus thediscovery of evolution is a good starting point for the history ofphylogenetics. While Darwin was not the first to propose that somespecies were genealogically related to others, it wasOn TheOrigin of Species (Darwin 1859) that convinced many biologists toaccept common ancestry and to start building phylogenies. One of theimmediate—and ongoing—impacts was the question this raisedin how phylogenies (i.e., reconstructions of evolutionary history)relate to taxonomies (i.e., how we group taxa).

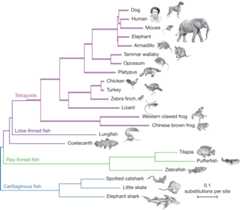

Figure 1 Phylogenetic (or evolutionary)trees have become commonplace in biology research articles. This treedisplays a recent hypothesis on the relative placement of lungfish andcoelacanth in the evolutionary history of tetrapods (Amemiya et al.2013: 312, fig. 1). [Anextended description of figure 6 is in the supplement.]

Pre-Darwinian taxonomy focused on classifying according to the“natural system” where taxa were united into large groupsdue to their “natural affinities” (Winsor 1976). In aneffort to clarify the concept of affinity, Richard Owen used the term“homologue” to refer to “the same organ in differentanimals under every variety of form and function” (Owen 1843).Put into an evolutionary framework, the natural affinities unitingthese groups were regarded as the result of descent with modificationfrom common ancestors and “homology” has since become acentral term in comparative biology (Donoghue 1992; Hall 1994). To seehow homology relates to phylogenetic inference, as well as tointroduce some basic terminology, it will be useful to consider anexample phylogeny (Figure 1).

Figure 1 provides a typical contemporary example of aphylogenetictree—a branching diagram that displays genealogicalrelationships. Phylogenetic trees like these include branches (thelines) and nodes (where the lines branch or come together, dependingon the direction you are reading the tree). Terminal branches aremarked with the entities whose evolutionary relationships are beingstudied. In this case those entities are species or higher taxa, buttrees may be constructed for other taxonomic levels, or any otherbiological entities whose evolutionary relationship can be studied(e.g., viruses, stretches of DNA, extinct taxa). Phylogenetic methodscan even be employed to study ontogeny or cultural evolution, e.g.,they have been used to construct cell fate maps to reveal how thedevelopmental parts of a single organism are related (Salipante &Horwitz 2006), and used to reconstruct the expansion of languagefamilies and help estimate historical human migration patterns (Gray& Jordan 2000; Gray & Atkinson 2003; Gray, Drummond, &Greenhill 2009). More recently, phylogenetic tools have been used toaid epidemiology studies of COVID-19 (Lemieux et al. 2021).

Since so much of modern biology requires the ability to readphylogenetic trees, good guides are commonplace. This includes journalarticles (e.g., Baum, Smith, & Donovan 2005; Baum 2008; Yang &Rannala 2012), online guides (e.g.,Understanding Evolution,Other Internet Resources), and more comprehensive textbooks (e.g., Felsenstein 2004; Lemey,Salemi, & Vandamme [eds] 2009; Wiley & Lieberman 2011; Baum& Smith 2013). Here, we provide only a brief introduction, butrecommend any of these (among others) to readers looking for a morethorough and technical introduction.

On the phylogenetic tree inFigure 1, time passes from left to right with extant groups labeled on theterminals of branches on the right.[1] Starting from the left there are two distinct branches, one leadingto Cartilaginous fish (sharks and rays), and the other to a node. Fromthat node the branches split, with one leading to Ray-finned fishes,and the other leading to another, more recent node (that ultimatelyleads to frogs, lizards, and mammals, among other taxa). Branches maybe read as representing ancestral lineages, with nodes representingcommon ancestors that diverged (or split) into distinct linealbranches.

We can also read the tree inFigure 1 by starting with the groups on the right and moving leftward, tracingbranches back to where they join at nodes. This direction takes usbackwards in time, and allows us to read off which groups are moreclosely related to others by looking at recency of common ancestry.For example, lungfish are more closely related to frogs than they areto pufferfish since lungfish and frogs share a more recent commonancestor with each other than either does with the pufferfish. To seethis, trace back along the branches from each group, starting on theright and moving left. You will converge on a node between thelungfish and frogs before reaching the node between either of thosetaxa and the pufferfish. Another way of saying this is that there is amonophyletic group (orclade) that includes lungfishand frogs that does not include pufferfish.

A monophyletic group consists of an ancestor and all of itsdescendants. Some familiar groups turn out not to be monophyletic. Forexample, if we tried to unite pufferfish and sharks into a singlegroup that excluded frogs and other tetrapods (such as the traditionalPisces) we get what is called aparaphyletic group.Individuals in paraphyletic groups all share a single common ancestor,but exclude some descendants of that ancestor. Artificial groups like“flying tetrapods” (birds plus the bats) would be calledpolyphyletic since they have multiple, distinct origins.Because paraphyletic and polyphyletic groups do not share a singlehistory that is unique just to them (i.e., there is no branch on thetree that leads just to this group), they cannot feature inexplanations in the same way that monophyletic groups can, i.e., theylack the utility and explanatory power of monophyletic groups (Velasco2008a). For example, biologists might be interested in studyingwhether flower diversity is driven by pollinator syndrome (i.e., moth,bird, or bee) or vice-versa. Phylogenetic principles predict differentpatterns of monophyly on these competing hypotheses, which can betested empirically and used by biologists as they design experimentsto test for the evidence of selection in cases like these (Whittall& Hodges 2007). This is simply unavailable without the explanatoryand organizing principles of monophyly, and one reason it has grown todominate systematics.

Each node on a tree is the origin of a monophyletic group. Forexample, the claim that the mammals form a single, united monophyleticgroup just means that all and only mammals share (i.e., are descendedfrom) a common ancestor. We have very good reasons to believe thatthis is true. For example, all and only the mammals have certaintraits (or characters) such as mammary glands, hair, and ossicles(three bones in the middle ear). Each of these traits arehomologues, i.e., their similarity is due to shared ancestry.(Homologous characters are typically contrasted withanalogouscharacters, i.e., traits whose similarity is not explained bycommon ancestry, but by some other process, e.g., convergent evolutionor reversal). The mammary glands in humans and in elephants arehomologous because the trait has been inherited from their commonancestor. Infigure 1, the ancestor of the mammals is located at the node with branchesleading to the platypus and the rest of the mammals. Once traitsemerge (as evolutionary novelties) on a branch they can be passed down(unchanged or modified) to the descendants of that lineage. Sinceplatypuses and mice have mammary glands, but no taxa stemming awayfrom earlier nodes do, we can infer that mammary glands evolved afterthe node where mammals and birds split, but prior to the mammaliannode. That is one way phylogenetic trees support inferential claims inbiology. If mammary glands had evolved prior to the node joiningmammals and birds, then we might expect to find mammary glands onbirds or lizards. Platypuses and mice are also born inside an amnioticsac, as are turkeys and lizards. However, frogs do not have anamniotic sac. This tells us that the amniotic sac evolved after thefrog lineage branched off from the other tetrapods. Parallel reasoningallows us to infer the history of the evolution of bones, tetrapodlimb structure, feathers, etc. These homologies form a nestedhierarchy of traits just as the monophyletic groups are nested, so,for example, the mammals are a part of amniotes which themselves are apart of the tetrapods. On the other hand, while the mammals and thebirds are both part of the amniotes, they do not overlap at all. Andindeed, no organisms have both mammary glands and feathers.

Explaining character distributions thus requires knowing which groupsare clades (i.e., monophyletic groups). Phylogenetic trees depictprecisely that, stating which groups are clades. This information iscalled thetopology of the tree, which conveys the relativeorder of the nodes and nothing about their absolute dating in time.Knowing which groups are clades allows us to reconstruct the evolutionof character traits, and it is the distribution of character traitsthat is the basic way that we infer which groups are clades in thefirst place. This style of reasoning (dubbed “reciprocalillumination” by Willi Hennig (1966) led to charges of circularreasoning from critics of phylogenetic inference (e.g., Sokal &Sneath 1963), whereas advocates have sought to explain why this worryis misplaced (see Wiley 1975; Sober 1988b, among many others). Infact, the nested hierarchies of traits is what led systematists toclassify taxa into a nested hierarchy in the first place, and it wasthe nested hierarchy of the taxonomic system that Darwin took to bethe most important evidence for common ancestry (Winsor 2009; Sober2009, 2010). The problems of understanding what it means for traits tobe homologous and of inferring homology will be discussed later (§2.1). Complicating things, groups of homologies do not always formunambiguous nested hierarchies, and sorting out what phylogenetichypotheses are best supported in these cases is a big part of whatgenerates debates over phylogenetic inference (more on this in§2 and§3.

Explaining character trait distributions is just the tip of theiceberg. Phylogenies are centrally important for all research inevolutionary biology. Phylogenetics lies at the heart of the linkingof the fields of systematics[2] and population genetics. Knowing a phylogeny is an important firststep to studying problems in evolutionary biology, functionalgenetics, comparative anatomy, and evolutionary developmental biology.Just as evolution is the unifying, organizing theme in biology,phylogenetics is the backbone of biological inference more generally.As Sterelny & Griffiths (1999: 379) put it, “Nothing inbiology makes sense except in the context of its place inphylogeny”.

1.2 From Darwin to Today: Three Interweaving Histories

For roughly 100 years after Darwin’sOrigin,phylogenetic research in biology was common and important. Yet,phylogenetics proceeded without much in the way of underlying theoryor explicable methodology—rather, the systematist with extensiveknowledge of some group simply relied on their judgment as to whichcharacter traits looked genuinely homologous and which charactertransformations seemed plausible. Some phylogenies were widely agreedupon due to the fact that when homologies are clear, inference iseasy. As early as the late 1800s, there was a general consensus amongsystematists around the branching order of many of the groupspresented inFigure 1. However, the relative placement of the coelacanth and lungfish wasdisputed almost immediately upon discovery of the former in 1938(Thomson 1991)—a dispute that has continued to draw attentionfrom biologists (e.g., Bockmann, De Carvalho, & De Carvalho 2013;Amemiya et al. 2013; Takezaki & Nishihara 2017).

The lungfish and the coelacanth appear key to understanding theorigins of the tetrapods, which has remained a major question in thereconstruction of evolutionary history since Darwin. But this is justone example among many. Bowler (1996) surveys the development ofphylogenetics over this time period and examines a number of thesedebates in more detail such as whether the arthropods form amonophyletic group, and the question of the origin of birds, and, inparticular, how they are related to the extinct dinosaurs.

While there are still important disagreements regarding phylogenies,the nature of these disputes have changed substantially asphylogeneticists no longer rely largely on individual expert judgment.The mid-twentieth century saw the introduction of competing accountsof the theoretical foundations of systematics (§1.2.1), a flurry of new algorithmic methods for constructing phylogenies andtaxonomic classifications, and the beginning of relatively easy accessto and employment of computational power (§1.2.3), all combined with new sources of evidence in the form of variouskinds of molecular data (§1.2.2). As biologists sought to incorporate these emerging features intophylogenetic method and theory, debates arose over how (or whether)this fundamentally changed the nature of systematics. At the sametime, debates about the foundations of systematics and the propermethods for classification and taxonomy became highly prevalent andinterwoven with arguments about these new methods and newly availabledata.

Traditionally, the emergence of phylogenetics has been presentedlargely in the context of debates between three major schools oftwentieth century taxonomic thought, often called “TheSystematics Wars” (§1.2.1). As centrally important as this was, a singular focus on that historyrisks overshadowing the impact of the molecular revolution (§1.2.2) and ever-increasing access to greater computing power (§1.2.3) on the establishment of phylogenetics. Below we consider how each ofthese twentieth century developments impacted the emergence ofphylogenetics as a distinct field of research. Yet, there are manyoverlapping themes cross-cutting these developments (often reinforcedby allegiances between individual researchers), suggesting that,ultimately, an integrated approach is needed for a rich, nuancedhistory of phylogenetics.

1.2.1 The Systematics Wars

Historically, phylogenetics emerged out of the larger field ofbiological systematics, the field of biology that studies thediversity of life and the relationships of living things through time.Today, systematists typically treat “relatedness” solelyin terms of recency of common ancestry, but this was not always thecase. Pre-Darwinian taxonomists discussed the relationships of variousgroups and their place in the “natural system”, and whilethe rise of evolutionary theory allowed that one sense of relatednesswas genealogical, it did not eliminate the idea of the broader notion.Debates about the role of phylogeny in classification and taxonomywere widespread (e.g., Huxley [ed.] 1940; Winsor 1995) though theybegan to take on a new form beginning in the late 1950s ascollaborations turned into organized research programs pushing theiragendas.

In his analysis of the period, David Hull (1988: ch. 5) titled one ofhis chapters “Systematists at War” and thus the name“The Systematics Wars” is sometimes used to describe thedebates of the period. Hull (1970) influentially compared three“contemporary systematic philosophies”, typically calledpheneticism, (ornumerical taxonomy, after theseminal Sokal & Sneath (1963) textbook of the same name),cladistics orphylogenetic systematics (afterHennig’s 1966 foundational text, an earlier version of which waspublished in German in 1950), andevolutionary systematics(following the lead of proponents like Simpson [1961] and Mayr [1969]and others).

The pheneticists disputed that we were in a position to know commonancestry with enough certainty to justify adopting it as foundationalto our notion of “relatedness”, and maintained that thetaxonomists’ job was discovering clusters of similarity (Sokal& Sneath 1963). Pheneticists were critical of what they viewed asthe entrenched approach to systematics, arguing that the traditionalapproach to selecting between hypotheses largely relied on therelative prominence or status of the biologist rather than goodscientific methodology. They explicitly framed their views in thecontext of arguments about what constituted “good science”and sought to promote independent and objective modes of assessingcompeting taxonomic groupings that relied on transparent andrepeatable methods. This included advocating for a greater separationbetween biological theory and the construction of similaritygroups.

Around the same time, another group (phylogenetic systematists)insisted that recency of common ancestry provided the besttheoretically-motivated foundation for relatedness (Hennig 1966). Likethe pheneticists, they too sought to promote good scientific methodsin systematics, and were similarly critical of established approaches.The phylogenetic systematists can be characterized by their insistencethat all taxonomic groups above the species level should bemonophyletic. Thus, if birds are descended from dinosaurs then theyare dinosaurs (Padian & Horner 2002). If the dinosaurs(or the reptiles more generally) are defined in a way that excludesbirds, then the group is paraphyletic and thus cannot be a taxon in aphylogenetic taxonomic system. Ernst Mayr derisively named them“cladists” for their obsessive focus on recovering clades(i.e., monophyletic groups) (Mayr 1965a), though its practitionerswere happy to embrace the name. When consistently carried out,phylogenetic taxonomic principles led to major revisions inlong-standing, traditional classifications—revisions that oftengenerated deep controversy (e.g., Halstead 1978; Gardiner et al.1979).

Both pheneticism and cladism were developed in opposition toentrenched views in systematics. In response, biologists committed tomore traditional methods sought to articulate the theoreticalunderpinnings of their approach, which came to be known asevolutionary systematics. With Ernst Mayr as their most prominentadvocate, evolutionary systematists sought to incorporate phylogenyinto classifications, but permitted that classifications might also(or even instead) represent important adaptive differences betweengroups (Simpson 1961; Mayr 1969). A prominent example that regularlyfeatured in these debates is the taxonomic placement of the birds andcrocodiles. Mayr argued that though birds are descended from dinosaursand reptiles more generally, birds share a cluster of adaptationswhich justify classifying them as a distinctive group at ataxonomically equivalent rank as reptiles. However, even thoughcrocodiles are more closely related to birds than to lizards and thusbelong to a clade with birds that lizards are not a part of, Mayrstill classifies crocodiles as part of the reptile“grade”—a group characterized by a well integratedadaptive complex (Mayr 1974). Thus unlike the cladists, evolutionarysystematists advocated for the inclusion of reptiles and otherparaphyletic groups in taxonomy.

One natural way to understand these debates is to recognize them assystematists sorting out “reconstructing a phylogeny” and“classifying a group of taxa” as two distinct tasks, andworking out how (if at all) these tasks ought to be reciprocallyinformative (Mayr 1965a, 1974; Griffiths 1974; Hennig 1975; de Queiroz& Gauthier 1990, 1992). With respect to this particular issue,cladistics has largely won; today when scientists designate highertaxa they are typically always describing monophyletic groups. Theprinciple of monophyly has proven to be such a powerful explanatoryand organizing tool that the commitment to it has grown widely and nowdominates systematics–in addition to informing both theory andmethodology across fields of biology This is one reason why thisperiod is sometimes referred to as “The CladisticRevolution” (Hull 1988; Kearney 2007; Haber 2009).

Yet, another framing is available. Namely, that as biologists shiftedto using phylogenies (rather than traditional taxonomies) to supporttheir explanations and justify their inferences, disagreements overtaxonomic classifications faded into the background. On this account,it is disagreements over phylogenetic hypotheses that are impactful;disputes over classifications become less consequential as they getreplaced in scientific inference by phylogenies. Joseph Felsenstein(2004: 145) dubs this the “It-Doesn’t-Matter-Very-Muchschool”, arguing that “systematists ‘voted withtheir feet’ to establish this school, long before I announcedits existence”. How phylogenetics ought to influence, inform, orconstrain taxonomic classifications is still a live debate (seeEreshefsky 2001 as well as debates over the adoption of the PhyloCode,among other debates about phylogenetic taxonomy), though one that isorthogonal to the inference of phylogenies. Contemporary debates ontaxonomic classification are largely over how to draw inferencesfrom phylogeniesfor classifications; there is verylittle dispute over the coherency of reconstructing phylogenies.Biological classification, on this account, is not viewed as acompetitor to phylogenetics, but dependent on it—and not theother way around. Phylogeneticists, like Felsenstein, can largelyproceed in reconstructing phylogenies without paying attention toclassificatory questions, though some of the metaphysical questionsabout the units of phylogenetics can come back to impact the inferenceof phylogeny itself (see§2.6.2)

As an important aside, we say ‘largely’ in the previousparagraph because—as in many cases in biology—there is notunanimity. Notably, biologists that identify aspatterncladists would dispute many of the chacterizations we haveoffered about phylogenetics, including the very first sentence of thisentry, i.e., “a phylogeny is a reconstruction of evolutionaryhistory.” Though there are a number of views that might beidentified with pattern cladism, all would typically regard that claimas unjustifiably reading a process into what is largely a claim aboutpatterns only. On pattern cladism, phylogenetic trees are typicallyregarded as graphical representations of evidence from characters; inthat regard, a phylogeny would just be a classification of thosecharacters. For the pattern cladist, directly inferring process orevolutionary history from phylogenies—or, worse, buildingevolutionary process assumptions into phylogenetic inference—isa mistake. They defend this for numerous reasons, often onphilosophical grounds, i.e., that pattern cladism embodies goodscientific inference, or that evolutionary claims require additionalinferential steps that need to be made explicit (Farris 1983). Thishas contributed to a split in the larger cladistics community. Oneupshot of this process/pattern split is that the term‘cladist’ has become ambiguous, contested, and imprecise,and it is not always clear who gets regarded as what kind of cladist(Carpenter 1987, The Editors 2016, Quinn 2017, Brower 2018a, Williamsand Ebach 2018). For example, while pattern cladists reject anyapriori assumptions about evolution (Brower 2019), so-calledprocess (or, sometimes,phylogenetic)cladists regard evolutionary claims as foundational tophylogenetics, while others (e.g.,statisticalphylogeneticists) have distanced themselves from using‘cladist’ as a label altogether (see§2.3 and the subsection§2.3.1 for more on this disputed taxonomy). We recommend that philosopherswriting in this area carefully specify the precise sense of‘cladist/m’, if they use that term at all, and cautionagainst using it interchangeably with ‘phylogenetics’.

Philosophers have largely focused on other topics in systematics thanthe pattern/process split. This is somewhat surprising as there arerich philosophical topics that could be fruitfully unpacked or drawnon as data by philosophers of science, especially for those interestedin the nature of scientific explanation and inference, or the role oftheory in biological methodology. For foundational literature onprocess versus pattern cladism see Beatty’s (1982) introductionof the designation of pattern cladism, with responses by Brady (1982),Patterson (1982), and Platnick (1982). Two good recent pattern cladisttextbooks include Williams & Ebach (2020) and Brower & Schuh(2021). There is an expansive though well contained literature withincladistics featuring debates between pattern and process cladists,e.g., Carpenter (1987), Brower (2000, 2002, 2019), and Lee (2002) arejust a very small selection of a large literature that philosophersinterested in the justification of scientific inference and methologymight explore.

Regardless of whether disputes about taxonomic philosophy died downbecause systematists came to agree or because they became lessimportant, it is a mistake for philosophers to treat the SystematicsWars as a live dispute, as opposed to an historical one. Yet, itremains an important episode in the history of systematics, and thecore conceptual debates left their mark on contemporary debates inphylogenetics (Haber 2009). At stake was not merely what notion of“relatedness” systematists ought to adopt, but whatconstituted good science in the context of inferring history andconstructing classifications, and the relative value (and evencoherence) of concepts like objectivity, testability, andrepeatability in science. But systematists no longer disputewhether phylogenetic inference may be justified as ascientific activity, but, rather, over how best to carry it out. Alarge part of why this change took place has to do with theavailability of new sources of molecular data and the introduction ofnew methods to take advantage of it. It is to this history that we nowturn.

1.2.2 The Molecular Revolution

Like Felsenstein, Sterner and Lidgard (2018) encourage historians andphilosophers of biology to “move past the systematicswars”. Their point is not that this was unimportant, but that asingular focus on it tends to overshadow the impact of other importanthistorical advances during this period. We agree. To remedy this,Sterner and Lidgard suggest paying attention to thepracticeof systematists in this period, rather than more narrowly focusing ondefinitional disputes (embodying the so-called philosophy of sciencein practice approach (Ankeny, Chang, Boumans, & Boon 2011)). Doingso reveals that alongside the Systematics Wars were the dualmethodological revolutions of the mathematization of systematics andthe incorporation of molecular data. These trends cut across theseparate schools of systematics, generating their own set ofcontroversies. This is particularly acute in phylogenetics, where therise of the use of mathematical and computational tools was bothenthusiastically embraced and deeply resisted. We start with a shortdescription of the impact of molecular data on phylogenetics, beforemoving to how mathematical and statistical tools were incorporatedinto phylogenetic methods insection 1.2.3 (for other histories on these topics see Dietrich 1994, 1998; Hagen2001; Sterner & Lidgard 2018).

Let’s first consider the appeal of including molecular data inphylogenetic analyses—perhaps even to the exclusion ofmorphological characters (e.g., Scotland, Olmstead, & Bennett 2003though see Wiens 2004). One of the most important aspects of themolecular revolution for phylogenetics was the sheer amount of newdata available to systematists, including for groups such as bacteria,where fossil data were scarce or severely lacking. Yet it was notmerely the scale and availability of molecular data that held suchappeal. As it became easier to collect, code, and collate these data,biologists argued that molecular phylogenetics provided an independentsource of evidence from morphological studies that bolstered evidencefor common ancestry and patterns of phylogeny (Zuckerkandl &Pauling 1965). In contrast, more traditional systematists such asTheodosius Dobzhanksy, Ernst Mayr and George Gaylord Simpson wereskeptical of molecular evolution studies quite generally, and, inparticular, the idea that they were in some way superior or couldreplace morphological studies (Dietrich 1998).

Many of the earliest molecular studies typically supported establishedphylogenies, e.g., Margoliash (1963) discusses the evolution ofcytochromec, though simply presumes the received phylogenyof species as correct. Later, Fitch & Margoliash (1967) constructa phylogeny solely from the cytochromec data, primarily todemonstrate molecular phylogenetic methods and how to test thereliability of results. Interestingly, one of the“anomalies” they mention is that turtles are placed closerto birds than to snakes—but this turns out to be no anomaly! Thevast majority of molecular studies have since placed the turtles as asister group to the archosaurs (a group which includes the birds andthe crocodiles) including the largest genome-scale studies done todate (Crawford et al. 2015).

The case of the phylogeny of turtles as well as other recent molecularstudies (e.g., of the lungfish and the coelacanth, see Amemiya et al.2013; Takezaki & Nishihara 2017) illustrate a general point. Evenin groups where we have extensive fossils and easily accessible livingspecimens with detailed anatomical and morphological studies,molecular evidence has often been taken to settle disputes and even tooverturn previously widely held views. This is in part due to thesheer volume of molecular data, which can overwhelm other sources ofevidence, but also because of the way molecular data may be viewed asevolving “neutrally”, i.e., as the result of mutation andgenetic drift rather than natural selection (Duret 2008), and, thus,be less prone to displayinganalogies (the result ofconvergent evolution), which can be mistaken forhomologies(the result of descent from common ancestry). (An analogy is thesimilarity relation between two analogous characters, and is a kind of“homoplasy” relation, i.e., characters whose similarity isnot due to descent from common ancestors.)

Analogies are false positives of evidence of common ancestry.Morphological traits, it is presumed, are more subject to selectivepressures that can generate these false positives, and so moleculardata from sources less subject to selective pressures (i.e., neutralsites) are preferable for reconstructing phylogenetic history. Fromthose phylogenies, analogies can be better identified, offeringevidence for appeals to natural selection (in the form of convergentevolution or other evolutionary processes) as an explanation for thepattern of biodiversity and trait distribution (Whittall & Hodges2007 provides a good example of this reasoning in regard to pollinatormode and morphology). Put another way, molecular data helps biologistsexplain why what appear to be homologies fail to form nestedhierarchies. Molecular data can identify which of those might beanalogies instead, and this helps resolve what would otherwise appearto be conflicts in phylogenetic inference. This is one way biologistsuse phylogenies to offer data-driven, theoretically-groundedevolutionary explanations, in contrast to “just-so”stories.

In addition to adding more evidence in cases where systematistsalready had a great deal of it, molecular studies can shed light oncases where other sources of evidence are extremely weak. For example,molecular data may preserve deep phylogenetic history otherwiseobscured at the morphological level by millions of years of adaptivechanges. Phylogeneticists depicting the very earliest branches inplant and animal phylogenies, as well as relationships between thedifferent groups of eukaryotes, recognized how molecular data couldboth test and enrich these deep phylogenetic hypotheses (Kenrick &Crane 1997; Baldauf 2003). Subsequent molecular phylogentic analyseshave demonstrated the fruitfulness of using molecular data (e.g.,amino acid sequences, RNA transcriptomes, and nuclear andmitochondrial genomes) for constructing deep phylogeny hypotheses(Heckman et al. 2001; Dunn, Giribet, Edgecombe, & Hejnol2014).

Emile Zuckerkandl and Linus Pauling’s introduction and use ofthe hypothesis of a molecular clock provides a good example of thepowerful utility of molecular data and was an important early episodein the history of molecular phylogenetics. The term “molecularclock” was coined in Zuckerkandl & Pauling (1965), but theyhad already used it without naming it in earlier publications(Zuckerkandl & Pauling 1962; Pauling & Zuckerkandl 1963). Thebasic idea is fairly simple. Given some estimated rate of molecularevolution, the relative ages of branches and nodes may be estimatedgiven some set of molecular data mapped onto a phylogenetic topology.Thus, molecular models of evolution were incorporated intophylogenetic methods (§1.2.3).

As more sequences of proteins became available, Zuckerkandl andPauling noted that homologous proteins displayed slight yetsystematically different sequences across taxa. For example, whilethere were 18 amino acid differences between the human and horsehemoglobin α-chains, there was thought to be only twodifferences between gorillas and humans.[3]

Zuckerkandl and Pauling then assumed that amino acid changes wereroughly linearly proportional to time, and thus the time between thedivergence of humans and horses was nine times greater than thatbetween humans and gorillas. Using paleontological estimates forcalibration, Zuckerkandl and Pauling concluded that the humans andgorillas diverged a mere 14.5 million years ago—much more recentthan traditionally was thought. This line of inference is not limitedto molecular phylogenetics, but has been imported for application toother data types, e.g., similar reasoning from phylogenetic techniqueshas been applied to language-tree divergence times to estimateIndo-European and Polynesian human migration (Gray & Jordan 2000;Gray & Atkinson 2003; Gray, Drummond, & Greenhill 2009). (Formore on the early development of the molecular clock, see Morgan1998.)

Later, it was thought that the neutral theory of evolution[4] provided some theoretical justification for the molecular clockhypothesis (Kimura 1968, 1969; Duret 2008), though Dietrich (1994)argues that the relationship goes in the other direction withZuckerkandl and Pauling’s research providing an essentialfoundation for the development of the neutral theory in the firstplace.

The molecular clock is but one of many examples of the importance ofmolecular biology to phylogenetics. Importantly, incorporatingmolecular data helped extend phylogenetic studies beyond eukaryotes,i.e., the molecular revolution has fundamentally altered (or,arguably, created) the field of microbial phylogenetics. Beginning in1969, Carl Woese began to sequence ribosomal RNA (rRNA) from acrossthe prokaryotic kingdom in an effort to understand bacterialphylogeny. The work was slow and difficult, but by 1975 Woese and hislab had sequenced the rRNA of 27 different bacterial taxa (Woese etal. 1975). In 1977, Woese and George Fox dropped a bombshell. They hadsequenced genes from a number of prokaryotic organisms whose rRNAgenes lacked the standard signatures of all previously known bacterialrRNA genes and which appeared as distantly related to the bacteria asdid the eukaryotes. Woese and Fox named them the“Archaebacteria” to emphasize their distinctness (Woese& Fox 1977). In 1990, Woese, Kandler, and Wheelis (1990) producedthe first attempt at building a universal tree of life that includedbacteria, archaebacteria, and the eukaryotes based on molecular data,with the project continuing to this day (Ciccarelli et al. 2006;Hinchliff et al. 2015; Hug et al. 2016). All of this is only possiblebecause of molecular sequence data.

1.2.3 The Mathematization of Phylogenetics and Introduction of Basic Phylogenetic Methods

The introduction of molecular data was highly significant inphylogenetics. In addition to the amount of data it generated, and theway molecular data provided evidence where other data were scarce,this new type of data was also significant in how it promoted themathematization of phylogenetics. Molecular data lends itself tomathematical and statistical analysis, in part due to (a) the ease bywhich molecular data may be encoded; (b) the systematic way molecularevolution may be mathematically modeled and subsequently incorporatedinto statistical methods; and (c) the manner by which mathematical andstatistical tools help analyze the large volume of molecular dataunder consideration. So though the molecular revolution andmathematization of systematics need not go hand-in-hand, it is hardlysurprising that they do.

A number of authors have discussed the rise of mathematical thinkingand computational tools in systematics—especially in connectionwith numerical taxonomy and phenetic classification (e.g., Hagen 2001;Sterner & Lidgard 2014, 2018). Here we focus on the rise ofstatistical methods for inferring phylogenies and later (§2) we discuss the philosophical debates that arose regarding the use ofthese methods. Good and more thorough textbook introductions forphylogenetic methods include Felsenstein (2004), Lemey et al. (2009)and Baum & Smith (2013). Yang and Rannala (2012) provide a helpfulrecent review in the context of molecular phylogenetics.)

Incorporating molecular data both encourages and is facilitated by theadoption of mathematical tools. We got a hint of that in thediscussion of molecular clocks (§1.2.2), which use estimated rates of molecular evolution to estimatedivergence times. Around the same time, Anthony Edwards and LucaCavalli-Sforza—both students of R.A. Fisher—began thinkingof phylogenetic inference as a problem for statistics. After initiallyworking independently on the problem, they collaborated to producewhat are perhaps the first set of papers presenting phylogeneticinference in a statistical framework (as attributed by (Felsenstein2001, 2004); Edwards’ own recollections of this work can befound in Edwards (1996)).

Among the earliest algorithmic methods for inferring phylogenies arethose known as “distance” methods. “Distance”could represent whichever character coding scheme we might be using toconstruct the tree, molecular or morphological, e.g., the number ofnucleotide differences between two sampled sequences of DNA. Adistance method uses these pair-wise distances to infer thephylogeny.

The first distance method developed is among the best justifiedstatistically, namely, theleast-squares method ofCavalli-Sforza and Edwards (1967). Here each topology has a set of“best-fitting” branch lengths where fit is measured bysumming the squared differences between the expected distance and theactual distance between each pair of taxa. The best tree topology isthe one whose best fit branch lengths are a better fit than any othertree’s best fit.

An alternative class of methods are known as parsimony methods. Herewe simply need a measure of how many steps it takes for one characterstate to transform into another. Recall that different tree hypothesesgenerate different explanations of the current characterdistributions. The basic idea behind parsimony is that the treehypothesis that explains these character distributions with the fewestnumber of evolutionary changes is to be preferred.

The first parsimony algorithm was published in Camin and Sokal (1965)and a number of variants of parsimony have since been developed. Forexample, one might want to weight certain kinds of changes relative toothers or even disallow certain kinds of changes (such as reversals)all together. A survey of such methods as well as a collection ofdifferent algorithms for carrying them out can be found in Felsenstein(2004). Parsimony was the chosen method for the Cladistic school whichis part of the reason that the history sketched in “TheSystematics Wars” (§1.2.1) above is intertwined with the history of mathematization sketchedhere. Philosophical arguments for and against the superiority ofparsimony as an inference method will be discussed later insection 2.3.

If we think of phylogenetic inference as an instance of statisticalinference more generally, then likelihood and Bayesian methods springto mind as methods that exemplify more general, statistical paradigms.Both require calculating probabilities and thus will require models ofevolutionary change i.e., some description of the process of evolutionand assignment of probabilities to possible changes in characterstates (such as from one nucleotide to another). Let’s brieflywalk through what that means, as how and whether to incorporate modelsof evolution in phylogenetic inference has been a major topic ofdebate.

If the data are observed nucleotide sequences from different groups ofterminal taxa, then the calculation we are after is the probabilitythat those observed sequences of nucleotides would arise on the tipsof competing phylogenetic hypotheses. The simplest way to calculatethat is to use the Jukes-Cantor model of evolution (Jukes & Cantor1969). This model assumes an equal frequency of the four nucleotides,and a uniform probability that any one nucleotide might change toanother. (These assumptions are typically violated, but reflectingthat in a model of evolution introduces additional parameters, whichincreases computing time—a valuable and limited resource in1969.) The Jukes-Cantor model provides a model of evolution on whichthe relevant probability that any given sequence might have evolvedfrom another more primitive sequence may be calculated. Different treetopologies will generate different probabilities that the observedsequences evolved from a hypothetical ancestral state. Thisconditional probability, \(P(\text{Data} | \text{Tree})\), is calledthe likelihood of the tree.

Though the Jukes-Cantor model is still used, more sophisticated modelsof evolution are available, e.g., the K80 (Kimura 1980), HKY85(Hasegawa, Kishino, & Yano 1985) and Tamura-Nei (Tamura & Nei1993) models of evolution. These introduce more parameters, e.g.,assumptions about equal frequencies of nucleotides and/or the uniformprobability of changing nucleotide states may be relaxed and evencustomized; models may also incorporate molecular clockassumptions.

These parameter-rich models reflect a better understanding ofmolecular evolution (e.g., that transversion and transition[5] rates between nucleotides are rarely equivalent) and the combinationof lowered costs and increasing accessibility to growing computationalpower that permits more parameter rich analyses. The large number ofmodels available leads to an interesting statistical problem in itsown right known as the problem of model selection, i.e., which modelof evolution do we use in our phylogenetic tools? For discussions ofthis problem in the context of phylogenetics, see (Posada &Crandall 1998; Sullivan & Joyce 2005; Posada 2008).

Once we choose a model or collection of models to work with, we cannow calculate probabilities conditional on these additional parameters(\(\theta\)). This likelihood may be formally represented as:

\[ L(\text{Tree}, \theta | \text{Data}) = P(\text{Data} | \text{Tree}, \theta) \]As a reminder, the likelihood of a hypothesis given a set of data isjust equal to the conditional probability of those data given thathypothesis. On these model-based phylogenetic approaches, the data areconditional on both a particular phylogenetic tree hypothesisand the stipulated parameters.

Using different values for the parameters in your model will lead todifferent likelihoods for the tree. The maximum likelihood estimate isthe tree hypothesis along with the fitted parameters which maximizesthis likelihood. Felsenstein (1981) gave the first computationallyfeasible algorithm for calculating likelihoods, and with moderncomputing power combined with the huge amounts of sequence dataavailable, likelihood methods have become the most commonly usedmethods in phylogenetics.

Just as with likelihood methods, Bayesian methods require a model ofevolution before any inferences are possible. The fundamentaldifference is that likelihood inference treats parameters of the modelas nuisance parameters which have a fixed but unknown value. In thefrequentist method of maximum likelihood, these parameters are set totheir best fitting value. Bayesian inference treats parameters asrandom variables with unknown distributions and probabilities are usedas a measure of uncertainty. The probability of a tree is aconditional probability \(P(\text{Tree} | \text{Data})\) under theassumption of a particular model. When we incorporate the modelparameters \(\theta\), by Bayes’ theorem, we have:

\[P(\text{Tree}, \theta | \text{Data}) = \frac{P(\text{Data} | \text{Tree}, \theta)*P(\text{Tree}) }{P(\text{Data})}.\]Controversially, this requires that we attach prior probabilities tothe possible hypotheses as well as the parameters in our model.Pickett and Randle (2005) claim that it is impossible to assign priorsin a consistent way. Velasco (2007) argues that this claim rests on amistake, though the problem remains a difficult one. He lateradvocates assigning priors to tree topologies, but leaves open themore difficult problem of priors on branch lengths or model parameters(Velasco 2008b). Alfaro and Holder (2006) attempt to address some ofthese issues.

Anthony Edwards (1970) was the first to discuss Bayesian methods inphylogenetics, but it was computationally impossible to carry theseinferences out at the time. In the 1990s, three groups independentlydeveloped methods for carrying out Bayesian inferences of phylogeniesin practice (Rannala & Yang 1996; Mau & Newton 1997; Yang& Rannala 1997; Li, Pearl, & Doss 2000). Each group usedBayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithms to estimateposterior probabilities, which other groups further refined (e.g.,Larget & Simon 1999; Ané, Larget, Baum, Smith, & Rokas2007; Huelsenbeck, Ané, Larget, & Ronquist 2008). (SeeArchibald, Mort, & Crawford 2003 for an early and non-technicalprimer on Bayesian phylogenetic methods.) With further statistical andcomputational improvements, Bayesian methods are now fairlycommonplace in the literature alongside likelihood methods.

2. Phylogenetic Inference and Philosophy

Section 1 served as an introduction to the history and problem of phylogeneticinference. In this section, we will look at how phylogenetics andphilosophy are intertwined—in particular, we will examine somefoundational debates in phylogenetics that have a distinctlyphilosophical flavor, and we will point out more traditionalphilosophical questions that the study of phylogenetics can shed lighton.

At its core, phylogenetic inference is about evaluating competinghypotheses. In an important sense, phylogeneticists are faced withwhat philosophers of science would identify as a problem ofunderdetermination of theory by evidence .Multiple competing phylogenetic trees can explain the same data,though in conflicting ways; it is the phylogeneticists task toidentify which of those hypotheses best explains those data. It willbe useful to separate the problem into two parts:

- identifying what the evidence is; and

- constructing a phylogeny to explain the evidence we have.

In the case of phylogenetic inference, we are in the philosophicallyinteresting and puzzling situation where it seems that these twoquestions cannot really be separated.

2.1 Alignment and Character Coding

The question of which method of phylogenetic inference is bestjustified is clearly important, but skips over an important step inphylogenetic inference—the construction of a data matrix ofcharacters. Mishler (2005), for one, argues that it is the mostimportant step! Following Winther (2009), we can separatecharacter analysis which results in the construction of adata matrix fromphylogenetic analysis which treats the dataas input and produces a phylogeny. This first stage of characteranalysis has been widely discussed in biology (though surely lesswidely discussed than the second stage). In addition to the voluminousliterature on homology, useful collections of work on charactersinclude those edited by Wagner (2000) and Scotland & Pennington(2000).

Character analysis includes identifying characters of the organisms weare looking at, and in particular, identifying when a character in oneorganism is the same character as in another organism. This is theproblem of homology. A different, but related problem, is assigningcharacter states. For example, one bear might have black fur whileanother has white fur. Here, “fur” is the character, butit is in a different state (fur color) in the two organisms. Though itis standard to treat characters and character states separately, theextent to which these are genuinely different problems rather thanthan aspects of the same problem is a matter of debate (Stevens 2000;Freudenstein 2005; Sereno 2005).

Identifying and coding characters is certainly a biological problem,but it is a philosophical one as well. On what basis can we judge thatone character is homologous to another? Debates on this extend back tothe very beginning of contemporary biology, e.g., Richard Owen’sinfluential pre-Darwinian notion of homologue to Ernst Haeckel workingto develop accounts of homology in the context of Darwinian evolution.In the mid-twentieth century, the pheneticists argued that characteridentification must be “theory-free” and advocated usingraw similarity as a guide to identifying homology (Sokal & Sneath1963; Sneath & Sokal 1973). There are well known philosophical andbiological problems with trying to use similarity in this way (e.g.,Goodman 1972), many of which were raised as objections to strictpheneticism during the Systematics Wars (e.g., Mayr 1965b; Neff 1986;Rieppel & Kearney 2002 though see Lewens 2012 for a recent defenseof pheneticism in a contemporary context).

In a phylogenetic context, homologies are regarded as the result ofdescent with modification from common ancestors. Similarity andidentity, in that context, is an expression of shared evolutionaryhistory. At the same time, homologies are also treated as hypothesesfrom which we can infer phylogenetic hypotheses (and, subsequently,both test and explain our hypotheses of homology). Clearly, even in acontemporary phylogenetic context, questions remain on how toindividuate characters and identify homologies. Richards (2002, 2003)worries that since there is no algorithm for individuating characters,we rely on illegitimate, nonscientific factors rendering characteridentification and phylogenetic analysis ultimately subjective.Rieppel and Kearney (2007) and Winther (2009) respond that characteranalysis can be considered objective since it relies on various kindsof causal criteria; Kendig (2016) adopts a slightly differentstrategy, rejecting the idea that we need to develop an analyticdefinition of “homology”, instead looking to biologicalpractice as a guide for individuating characters.

While character analysis and phylogenetic analysis are logicallyseparate tasks, in theory they should be intertwined. A givenphylogeny can make an assessment of homology more or less plausible.One proposal to avoid this problem is the introduction of adistinction between “primary” homologies (an initialcharacter identification based on structural features) and“secondary” homologies (similarity due to common ancestry)which are inferred through phylogenetic analysis (Pinna 1991; seeRoffe 2020 for a recent philosophical treatment of this distinction).On the other hand, Rieppel and Kearney (2002) argue that characterhypotheses need to be independently testable and phylogenetic analysiscan clearly provide evidence for miscoding of characters—even ifthis is not the intended goal.

Molecular data presents a different set of challenges forindividuating characters and coding them into a matrix, nicelyillustrated by DNA sequence data. With only four base nucleotides,coding is easy (§1.2.3), and modern laboratory techniques provide highly reliable sequences ofnucleotides in a stretch of DNA. But here, the problem isalignment. How do we know that one stretch of nucleotidesequences should correspond to similar stretches in other taxa? Wemight consider chromosomal location, or even functional similarities,though each of these raise other questions of how we decide what oughtto be treated as homologous characters (even contingently) acrosstaxa. This becomes even more complicated as we consider how historicalprocesses like gene duplication/loss or recombination add complexityto these questions. This is the problem of positional homology. Likemorphological character coding, molecular alignment is intertwinedwith phylogenetic analysis and various methods of joint inference havebeen proposed (Redelings & Suchard 2005; Wheeler et al. 2006).

2.2 Computational Limits and Big Data

Bearing in mind what we said above about the interconnectedness ofcharacter analysis and phylogenetic analysis, we will now proceed tothe second part, analysis of the data. At this stage, computationallimits loom large. Even if we are concerned only with inferring thetopology of a phylogeny, the number of possible trees growsexponentially relative to the number of terminal branches we includeon a tree. The formula for calculating the number of possible treetopologies is relatively straight-forward (Felsenstein 2004):

\[\frac{(2n-3)!}{2^{n-2}(n-2)!}\]wheren is the number of taxa. The upshot is that even asmall expansion of terminal branches results in an exponentialincrease in the number of possible topologies. So, for example, thereare 15 possible phylogenetic trees for a group of 4 species, over 34million for 10 species, and \(8 \times 10^{21}\) with 20 species.[6]

This means that exhaustive evaluation of all possible hypotheses veryquickly becomes all but impossible—even as our capacity for thishas grown with increased computing power. Finding the mostparsimonious tree, the maximum likelihood tree, and even doing amultiple sequence alignment to begin with are all NP-complete problems[7] (Graham & Foulds 1982; Wang & Jiang 1994; Chor & Tuller2005). Bayesian inference is similarly computationally intractable(Ronquist, Mark, & Huelsenbeck 2009).

In response, researchers have developed heuristic search strategies toexplore possible tree space. For example, in Bayesian analysis theprobability space of possible trees is so large that starting byrandomly selecting a tree will be highly inefficient. It will almostsurely fail to provide a good estimate of the posterior probabilitydistribution, since the interesting regions will only occupy a smallpart of that distribution space (Ronquist et al. 2009). A commonheuristic is to start with a parsimony or distance-methods tree.Though these methods typically perform worse than model-basedapproaches, they are much less computationally expensive and canquickly generate an initially plausible tree that Bayesianphylogeneticists use as a launching off point to explore the treeprobability space (e.g., using hill-climbing algorithms such as MarkovChain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling). Innovations like these are onereason that computational phylogenetics is an important field in bothstatistics and computer science. Philosophers of science interested inhow scientists explore and use so-called “Big Data” wouldprofit from examining how phylogeneticists have developed, adapted,and employed heuristic search strategies.

Setting aside computational and practical problems leaves us with whatappears to be a straightforward epistemological question—whichmethods are best justified in licensing phylogenetic inferences? Webegin our examination of this question by looking at arguments infavor of a particular method, parsimony.

2.3 Justifications of Parsimony

Parsimony methods were among the very first adopted by cladists. Thisis often taken to include Hennig (1966), who laid out a process ofphylogenetic inference that is now referred to as “Hennigianreasoning” in his seminal textPhylogenetic Systematics(Baum & Smith 2013). Like other forms of parsimony, this methodsought to identify the tree that explained the distribution ofhomologies by appeal to the fewest number of evolutionary events.

Parsimony techniques have grown more sophisticated, and, as largerdata sets have been assessed and bigger trees constructed,justifications of parsimony approaches advanced and adapted. Early on,much of this took place in the context of the Systematics Wars (§1.2.1), where a premium was placed on defending approaches as properlyscientific. Thus, these debates tended to veer into philosophy ofscience, with systematists disputing what counted as doing goodscience in the context of inferring history. This helps explain theinfluence ofKarl Popper’s work. Earlyproponents of parsimony were attracted to Popper’sfalsificationist account of the scientific method, both in the way itprovided demarcation criteria for scientific activity, and in the wayit was positioned as critical oflogical positivist approaches. Falsificationist justifications were employed to criticizenumerical taxonomists as verificationists relying on flawedhypothetico-deductive methods.

Wiley (1975) provides a representative example of a falsificationistdefense of parsimony that proved deeply influential, e.g., Eldredge& Cracraft (1980) adopt Wiley’s core justification in theirinfluential textbook, as does Farris (1983) in his impactful defenseof parsimony. On Wiley’s account, each taxonomic character istreated as an homology, and considered independently of all others.For each homology, a tree hypothesis is generated that requires thefewest number of evolutionary changes to explain the pattern ofcharacter distribution across taxa. These are hypotheses of homologyand, on the falsificationist account, these hypotheses are mutuallytestable. That is, the tree hypotheses generated for each characterconstitutes a test of the trees hypothesized for every othercharacter; falsified hypotheses of homology are treated as ad hocassumptions of homoplasy. The maximum parsimony tree is that topologywhich generates the fewest falsified hypotheses of homology, and isregarded as the most corroborated tree. Adding new characters or taxaconstitutes further testing of these hypotheses, and generates morepotential falsifiers. In this way, parsimony is simultaneously a modeof tree construction and evaluation (Haber 2009); Wiley (1975),Eldredge and Cracraft (1980), and Farris (1983) describe this as alogical basis of reasoning about phylogenetic inference, citing thephilosophical justification of falsificationism.

Whether this represents a faithful account of Popper’sfalsificationism, or whether falsificationism representstheoptimal (or even a desirable) mode of scientific reasoning has been amatter taken up by philosophers (Hull 1983, 1999; Sober 1988b), thoughthat is, in some ways, beside the point. (For a philosophically-mindedbiologist’s survey of the role of Popper in systematics, seeGaffney 1979, Rieppel 2008, or Santis 2020.) Regardless,characterizing parsimony in falsificationist terms provided animportant justification that resonates to this day. More recentinvocations of Popper in phylogenetic inference have focused onwhether parsimony or model-based methods such as Maximum Likelihood (§1.2.3) better align with falsificationism (e.g., Siddall & Kluge 1997;de Queiroz & Poe 2001, 2003; Kluge 2001), and whetherprobabilistic and statistical reasoning is relevant for studyingsingular historical events (Siddall & Kluge 1997; Haber 2005).(See Turner 2007; Cleland 2011;Currie 2018, 2019, for generalphilosophy of historical science.) Insection 2.4 we describe how Felsenstein’s (1978) discovery that parsimonyis prone to systematic errors poses a serious challenge to thisunderlying falsificationist justification.

Parsimony can be defended without falsificationism, and otherjustifications have been offered that appeal to the method’snamesake, i.e., the principle of parsimonious reasoning or appeals toOckham’s Razor (e.g., Kluge 2005). It amounts to (i) defendingparsimony (the principle) as the criterion by which we ought to assesscompeting phylogenetic hypotheses, and (ii) arguing that parsimony(the method) is the best mode for achieving that goal by seeking outthat tree that minimizes the number of evolutionary novelties requiredto explain the distribution of characters. This may also be presentedas identifying that tree that minimizes the number of ad hocassumptions of homoplasy. Though this appeal to simplicity may bewedded to falsificationist justifications (as we saw above), they arelogically independent defenses. There is certainly an intuitive appealto the principle of parsimony in the sciences, and Ockham’srazor remains influential for good reason. But justifying parsimonymethods by appeal to simplicity is not so straight-forward. Evaluatingwhich phylogenetic approaches are justified by Ockham’s Razordepends on what is being counted (Haber 2009). Sober (1988b, 2015among others) provide useful discussions of the role of simplicity andthe principle of parsimony in phylogenetics.

Other philosophical justifications of parsimony have been offered.Fitzhugh (2008 and elsewhere) has argued that the problem ofphylogenetic inference is best understood as an abductive problem, andthat treating it as a problem for statistical (or inductive) inferenceamounts to a category error. Sober (1988b) agrees that phylogeneticsinvolves abductive reasoning, though argues that thisjustifies the use of statistical approaches (especiallylikelihood).

It is also worth recalling why pattern cladists in particular objectto model-based methods of phylogeny reconstruction. Pattern cladiststypically rejectany method of phylogeny reconstruction thatincludes assumptions about the evolutionary process (§1.2.1),e.g., Brower (2019: 717) identifies a centrral commitmentdistinguishing pattern from process (or traditional or phylogenetic)cladism as the rejection of “a priori evolutionarybackground assumptions from the inference of patterns of relationshipsamong taxa.” As such, pattern cladists have strongly objected tolikelihood and other model-based phylogenetic methods, as thoseexplicitly incorporate evolutionary models (§1.2.3 and§2.4). This has typically gone hand-in-hand with a rejection ofstatistical approaches more generally, and a commitment to parsimony,e.g., “the statistical approach to phylogenetic inference waswrong from the start, for it rests on the idea that to study phylogenyat all, one must first know in great detail how evolution hasproceeded. That cannot very well be the way in which scientificknowledge is obtained” (Farris 1983: 17).

In response, statistical phylogeneticists have argued that parsimonymethods implicitly include evolutionary models, which model-basedmethods simply make explicit and, thus, subject to interrogation (deQueiroz & Poe 2001, 2003; Swofford & Sullivan 2009). Thisfault line is further reflected in the way pattern cladists view otherproponents of parsimony as allies in this debate, as Brower (2019:717), approvingly citing Kluge & Farris (1999), makes clear:“despite this difference of opinion regarding criticalbackground knowledge, there is no practical distinction betweenpattern and process cladists’ evidence, analyses or results.From a methodological perspective, all cladists group by synapomorphyalone.” That is, it is in the interpretation of methodology andinferential justification that distinctions are drawn between patternand process cladists; in the larger debate with statisticalphylogeneticists they are allied. Note, however, that ever finerdistinctions of the term ‘cladist’ are being introduced(let alone ‘statistical phylogeneticists’, who typicallyassociate with model-based approaches). This reflects the way thisterm has grown contested and associated with various competing sets ofcommitments. It is worth taking a brief detour in section 2.3.1 tosort through this a bit.

2.3.1 Who Owns the Term “Cladist”?

Insection 1.2.1, we used the term “cladistics” to refer to a school oftaxonomy which held that higher taxa must be monophyletic, and stoodin contrast to the competing schools of phenetics/numerical taxonomyand evolutionary taxonomy. In this historical context,“cladistics” was sometimes used interchangeably with“phylogenetics”. We caution against that practice,especially when discussing more contemporary practices. Though it ishard to pin down a precise date when these terms began to carrydifferent connotations, Felsenstein (1978) and Beatty (1982) are asgood a marker as any for when these terms began to diverge and take onmore nuanced senses. This is particularly true of the term“cladist”, which has become a highly disputed term, andone that has been claimed by sub-groups within the larger field ofphylogenetics.

An apt example of this is the journalCladistics, whoseeditors published a controversial editorial in 2016 stating thatsubmitted manuscripts should reflect the philosophical commitments ofthe journal and its sponsoring professional society (The WilliHennig Society) (Editors 2016). They write,

The epistemological paradigm of this journal is parsimony. There arestrong philosophical arguments in support of parsimony versus othermethods of phylogenetic inference (e.g., Farris 1983).

The editorial continues, stipulating that “Phylogenetic datasets submitted to this journal should be analysed usingparsimony”. If trees generated by alternative methods showdifferent results, these may be included if authors prefer thosetopologies, but only if authors are “prepared to defend it onphilosophical grounds” (all quotes from Editors 2016: 1). Theeditors, here, are using the imprimatur of the journalCladistics to stake out a specific sense of how“cladistics” ought to be understood, and what callingoneself a “Cladist” signals about the underlyingtheoretical and philosophical commitments held about phylogeneticinference, i.e., an exclusive commitment to parsimonymethods—going so far as to reject model-based statisticalapproaches entirely.

Aleta Quinn (2017) argues that the term “cladist” remainsone claimed by multiple overlapping (yet importantly distinct) camps.She tackles the ambiguity head on, providing a useful “foreignlanguage dictionary” of ways that “cladist” getsused in systematics. Quinn argues that the term is in need ofdisambiguation, drawing seven different senses from the literature.This includes systematists that advocate adherence to particularphylogenetic methods (e.g., parsimony, as in the case of theCladistics editorial) or philosophical justifications(especially to a version of Popperian falsificationism), though thevarious distinctions of competing senses of “cladist” gowell beyond this. In response to Quinn, Williams and Ebach (2018)propose an eighth (and their preferred) sense of cladist, and Brower(2018a) offers a focused commentary on Quinn’s article, as wellas other attempts to clarify the philosophical foundations andcommitments of pattern cladism. For example, a distinguishing featureof pattern cladism is the rejection ofa priori assumptionsabout evolutionary theory in phylogenetic methods. This has beeninterpreted as a claim of theory-neutrality or minimality by somephilosophers and biologists (e.g., Pearson 2010). Brower (2019)contests this interpretation, arguing that the claim of theoryneutrality is specific to evolutionary assumptions, as opposed to amore general claim.

The primary take away is that care should be taken when philosophersuse the term “cladist”. Though there are a lot ofinteresting philosophical topics to unpack around this term, it mustbe acknowledged that it has become ambiguous. There are simply toomany senses of this term for it to be used without clearly specifyingprecisely what sense is being invoked. We encourage philosopherswriting about phylogenetics to follow the lead of systematists, andavoid using the terms “cladist”, “cladistics”,and other cognates as synonymous with “phylogenetics”.Instead, philosophers should reserve usage of those terms andcarefully specify which sub-set of phylogeneticists (or their work)those terms are referring to.

2.4 Long-Branch Attraction and model based methods

Insection 2.3 we mentioned that the falsificationist justification of parsimony wasmet with a serious challenge by the discovery that it was subject tomaking systematic errors under certain conditions. JosephFelsenstein’s (1978) paper, “Cases in which Parsimony orCompatibility Methods Will be Positively Misleading” firstdescribes what came to be known as the phenomenon of“long-branch attraction”. Though hardly the beginning ofdebates between parsimony and model-based phylogenetic methods, itrepresents an important inflection point in discussions aboutphylogenetic inference.

Long-branch attraction refers to the tendency of some methods topreferentially group together long branches (those with moreevolutionary changes) regardless of their actual history. Methodsdesigned to identify trees requiring the fewest number of evolutionarychanges to explain the data will prefer explanations of sharedancestry over convergent evolution—even in cases whereconvergent evolution occurred. For example, imagine two branches withrapidly evolving DNA sequences. By chance alone, the two branchesmight have the same mutation at the same site which parsimony treatsas evidence that these branches share a recent history. In a range ofcases, the chances of these similar mutations occurring is so highthat we expect the number of these convergent cases to overwhelm thesignal from the true homologies. In these cases, the parsimony methodis statistically inconsistent. A method is statistically consistentwhen it is guaranteed, as more data are added, to identify the correctsolution. Methods that fail to do this are statistically inconsistent.In this case, not only does parsimony fail to be consistent, but themethod reliably returns increased support for a specific, incorrectoutcome as more data are added and hence is “positivelymisleading”.

Long-branch attraction is more than just an operational problem, italso challenges the falsificationist underpinnings of parsimony (Haber2009). Recall that on Wiley’s (1975) influential account,phylogenetic trees are subject to being falsified as more data(characters) are discovered or added (§2.3). If a more parsimonious tree is available to explain those data, thepreviously most parsimonious tree is treated as falsified (or ascontaining more ad hoc hypotheses of homoplasy). Felsenstein’sdiscovery was that in some circumstances, as more characters areincluded in a parsimony analysis, parsimony will be prone to rejectinghypotheses that report the actual phylogenetic relations, whilecorroborating more parsimonious—but incorrect—phylogenetichypotheses. This undermines the logical justification of parsimonyanalysis.

Felsenstein (1978) was (and remains) an immensely impactful paper,generating numerous research programs. It is a largely theoretical andabstract paper that considers how different methods perform underdifferent biological conditions. One natural question that might beposed concerns how prevalent these conditions are in the actualsystems being studied. This is an empirical question, of course, andcan be studied as such, though disputes over how to interpretempirical cases have proven controversial (Huelsenbeck 1997; Whiting1998; Siddall & Whiting 1999; Yang & Rannala 2012).

In the 1990s experimental phylogeneticists used empirical andsimulation studies to more rigorously empirically test claims ofperformance of competing phylogenetic methods. This included testingcompeting methods to reconstruct known in-vivo phylogenies (ofbacteriophage) that were carefully constructed, tracked, and archivedover many generations and more complex simulated phylogenies (takingadvantage of the ever-growing processing power available on the labbench) (Hillis, Bull, White, Badgett, & Molineux 1992; Hillis& Bull 1993; Hillis, Huelsenbeck, & Cunningham 1994). Theselargely confirmed that distance and parsimony methods were subject tolong-branch attraction, where model-based statistical methods such aslikelihood avoided these epistemic traps.

2.5 Phylogenetics & Philosophy of Statistics

Felsenstein’s (1978) paper is also impactful because of hiscommitment to statistical consistency asthe standard bearerfor evaluating competing statistical approaches. For Felsenstein andmany other phylogeneticists, showing that parsimony is statisticallyinconsistent is a fatal blow. But not everyone agrees. In fact, someauthors argue that it is close to an irrelevant consideration. We nowturn to this debate about the importance of consistency as an exampleof how philosophy plays a central role in phylogenetic theory.

Like Edwards and Cavalli-Sforza before him, Felsenstein (1978) treatsphylogenetic inference as a problem for statistics. Jerzy Neyman(1971) pointed to the emerging field of molecular phylogenetics as asource of novel and interesting statistical problems. In theintervening fifty years the field has only expanded in importance tothe point where phylogenetic inference is now one of the centralproblems in statistics. Similarly, research on algorithms forinferring phylogenies has been important in computer science fordecades.

If phylogenetic inference is seen as a problem in statisticalinference, it might be thought that general arguments for idealstatistical methods will just apply in this case. Maximum likelihoodor Bayesian methods could be defended on these grounds for example. Inthis light, parsimony is a statistical method and as such, we canstudy its statistical properties (Felsenstein 1983, 2004). AnthonyEdwards (1996) claims that his initial usage of the “minimumevolution” principle was as an approximation to the maximumlikelihood solution which he believed to be justified on general,statistical grounds, i.e., parsimony methods could be assessed as astatistical approach. Since that time, a number of authors have shownexact connections (ordinally equivalent rankings) between parsimonyand likelihood in a range of cases (Felsenstein 1973; Sober 1985;Tuffley & Steel 1997; Steel & Penny 2000).

In an exchange on parsimony and likelihood between Felsenstein andElliott Sober, Felsenstein defends the idea that consistency “isa fundamental property” and in particular, that it is morefundamental than likelihood (Felsenstein & Sober 1986). Hereiterates his earlier claim that

maximum likelihood methods are not desirable in themselves, butbecause they have desirable statistical properties such as consistencyand asymptotic efficiency. (Felsenstein 1978: 408)

With this attitude, Felsenstein is merely following an old andvenerable position in statistics. For example, Fisher (1956: 141)called consistency “the fundamental criterion ofestimation” and said that inconsistent estimators are“outside the pale of decent usage” (Fisher 1935 [1950:11]). Neyman (1952: 188) agrees.

Contrary to Felsenstein’s position, Sober claims that

One does not “justify” a method by showing that there isan extremely special case in which it does its work well; nor does one“refute” a method by showing that there is another specialcase in which it makes a hash of things. (Sober 1988b: 76)

One particular argument that he gives against consistency is that itcan conflict with likelihood. Sober (1988a) presents an example inwhich likelihood inference can fail to be consistent. But Soberfollows Anthony Edwards (1972) in positing that likelihood is a“primitive postulate” which does not need justificationbased on repeated sampling. If a likelihood inference can fail to bestatistically consistent but is still justified, then clearlyconsistency cannot be a necessary criterion of justifiedinference.

A different kind of worry about consistency is expressed by authorswho point out that it is not clear what consistent method we coulduse. As the editors ofCladistics put it in their editorialdefending the use of parsimony,

we do not consider the hypothetical problem of statisticalinconsistency to constitute a philosophical argument for the rejectionof parsimony. All phylogenetic methods, including parsimony, mayproduce inconsistent or otherwise inaccurate results for a given dataset. (Editors 2016)

Maximum likelihood estimation is known to be provably consistent undera wide variety of conditions (Wald 1949), but several authors haveargued that these conditions do not apply to estimating the treetopology since tree topologies are discrete, not continuous,parameters (Yang 1996; Siddall 1998; Farris 1999). However, Swoffordet al. (2001) argue that Wald’s conditions do apply and Yang(1994), Chang (1996), and Rogers (2001) prove that maximum likelihoodis consistent under different assumptions about character evolution.But regardless of which assumptions suffice for likelihood to beconsistent, some assumptions about the evolutionary process aredefinitely required. But what happens when the model we use is not thecorrect model? This is especially problematic when combined with theview that to be a correct model it should be true, and that we couldnever know that our model was true or perhaps even that there is nosuch thing as a true model, as some pattern cladists have claimed(e.g., Brower 2016, 2018b). As Felsenstein (2004: 272) puts it,

likelihood is usually consistent if we use the correct model in ouranalysis. When we use the wrong model, there are few guarantees.

2.6 Phylogenetics and Philosophy