Petar Zrinski Peter IV Zrinski Zrínyi Péter | |

|---|---|

| Ban of Croatia | |

| |

| Ban of Croatia | |

| Reign | 24 January 1665 – 29 March 1670 |

| Predecessor | Nikola Zrinski |

| Successor | Miklós Erdődy |

| Born | (1621-06-06)6 June 1621 Vrbovec,Kingdom of Croatia, (todayCroatia) |

| Died | 30 April 1671(1671-04-30) (aged 49) Wiener Neustadt,Archduchy of Austria, (todayAustria) |

| Buried | Zagreb Cathedral,Croatia |

| Noble family | House of Zrinski |

| Spouse | Katarina Zrinska |

| Issue | Jelena Zrinska Ivan Antun Zrinski Judita Petronila Zora Veronika |

| Father | Juraj V Zrinski,Ban of Croatia |

| Mother | Magdalena Zrinska (bornSzéchy) |

Petar IV Zrinski (Hungarian:Zrínyi Péter) (6 June 1621 – 30 April 1671) wasBan of Croatia (Viceroy) from 1665 to 1670, general and a writer. A member of theZrinski noble family, he was noted for his role in the attempted Croatian-HungarianMagnate conspiracy to overthrow theHabsburgs, which ultimately led to his execution for high treason.

Petar Zrinski was born inVrbovec, a small town nearZagreb, the son ofJuraj V Zrinski and Magdalena Széchy. His father Juraj VI and great-grandfatherNikola IV had beenviceroys orBan ofCroatia, which was then a nominal Kingdom inpersonal union with the Hungarian Kingdom. His brother was the Croatian general and poet Nikola VII Zrinski.

His family had possessed large estates throughout all of Croatia and had family ties with the second largest Croatian landowners, theFrankopan family. He marriedAna Katarina, the half-sister ofFran Krsto Frankopan, and they lived in large castles ofOzalj (inCentral Croatia) andČakovec inMeđimurje, northernmost county of Croatia. Through his daughter, Jelena Zrinska, he was the grandfather of famed Hungarian generalFrancis II Rákóczi.

He was initially schooled abroad inGraz andTrnava, and later also studied military science inItaly. Upon his return in 1637, he clashed with the Ottomans nearNagykanizsa. Since then he resided inOzalj, where he marriedAna Katarina Frankapan. Due to forceful seizure of a land parcel nearRijeka, he was accused of treason, but was later pardoned in 1647. He was appointed a great captain ofŽumberakuskoks, with whom he participated in theThirty Years' War, in which he distinguished himself during its final phase on the German and Bohemian frontiers.[1]

In 1649, he defeated an Ottoman army nearSlunj, and in 1654, he aided theRepublic of Venice both on land and on sea in theCandian War, causing great damage to the Ottomans. In 1655, he again defeated an Ottoman army nearPerušić in Lika, which earned him the position of captain ofSenj,Ogulin and whole of Primorje (coastline).[1]

On 16 October 1663, he achieved his greatest victory against the Ottomans, in a place called Jurjeve Stjene (George's cliffs), nearOtočac, where hedefeated a much greater Ottoman army numbering 8,000-10,000 troops[2] under the command ofAli-Pasha Čengić, who was consequently captured by the Croatian army.[1] As a result, the entire army of theBosnia Eyalet was defeated, and invasions intoGacka from there permanently ceased. In spite of this success, the ransom for Čengić was taken away from him upon the complaint of general Herbert Auersperg, who previously withdrew toCarniola fromKarlovac.

The first large-scale manufacturing of iron-based goods on Croatian soil was established by Petar IV Zrinski on his estates inČabar,[3] where he built a smelting furnace, foundry and forge in 1651.[4][5] Theironworks facility employed hundreds of artisans and serfs producing goods such as nails, swords and plows, as well as other tools for various fields, and was in operation until the late 18th century.[6][7] The iron products produced there were then transported all across the land, but were also exported through the Zrinski-controlled port inBakar. In Bakar, awarehouse had also been built for this purpose.[8] In one such example, the goods were traded for salt with the merchants fromNaples.

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification. Please helpimprove this article byadding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.(April 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

During theAustro–Turkish War (1663–1664) Petar Zrinski fought the Turks at thesiege of Novi Zrin Castle along with his brotherNikola. After the unpopularPeace of Vasvár (1664) betweenHoly Roman Emperor Leopold I and theOttoman Empire, he joined Croatian and Hungarian nobility who were disappointed by the failure to remove the Ottomans completely from Hungarian territory and embarked on a conspiracy to remove foreign influence, includingHabsburg rule, from the Lands of theCrown of St. Stephen.

Petar Zrinski was involved in the poorly organized rebellion together with his older brother Nikola Zrinski and his brother-in-lawFran Krsto Frankopan and Hungarian noblemen. In the preparations of the plot, plans were disrupted by the death of Nikola Zrinski in the woods nearČakovec by a wounded wild boar. Later rumours insisted that he had in fact perished not in this accident but at the hands of murderers loyal to Habsburg rule; nevertheless this claim remained unsubstantiated. Petar succeeded his brother asBan of Croatia.

The conspirators, who hoped to gain foreign aid in their attempts, entered into secret negotiations with a number of nations: including France, Sweden, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Republic of Venice, even the Ottoman Empire. All such efforts proved unavailing – in fact, theHigh Porte informed Leopold of the conspiracy in 1666.[9] It turned out, also, that there was at least one pro-Austrian informant among the rebels. As a consequence the plans for an uprising had made little headway before the conspirators were arrested.

Zrinski and Frankopan, unaware of their detection, nevertheless continued planning the plot. When they tried to trigger a revolt by taking command of the Croatian troops, they were quickly repulsed, and the revolt collapsed. Finding themselves in a desperate position, they finally went to Vienna to ask emperorLeopold I of theHabsburg dynasty for pardon. They were offeredsafe conduct but were arrested. A tribunal chaired by chancellorJohann Paul Hocher sentenced them to death forhigh treason on 23 and 25 April 1671.[10]

For Petar Zrinski the verdict was read as follows:

Zrinski and Frankopan were executed bybeheading on 30 April 1671 inWiener Neustadt. Their estates were confiscated and their families relocated – Zrinski's wife,Katarina Zrinska, was interned in theDominican convent inGraz where she fell mentally ill and remained until her death in 1673, two of his daughters died in a monastery, and his sonIvan Antun (John Anthony) died in madness, after twenty years of terrible imprisonment and torture, on 11 November 1703. The oldest daughterJelena, already married in northeasternUpper Hungary, survived and continued the resistance.

Some 2,000 other nobles were arrested as part of a mass crackdown. Two more leading conspirators –Franz III. Nádasdy, Chief Justice of Hungary, andStyrian governor, CountHans Erasmus von Tattenbach – were executed (the latter inGraz on 1 December 1671).[12]

In the view of Emperor Leopold, the Croats and Hungarians had forfeited their right to self-administration through their role in the attempted rebellion. Leopold suspended the constitution – already, the Zrinski trial had been conducted by an Austrian, not a Hungarian court – and ruled Hungary like a conquered province.[13]

His final letter addressed to his wife before his execution was titled "Moje drago Zercze" (My dear heart) and had been translated by contemporaries to German, Hungarian, Dutch, French, Italian, English, Latin and Spanish languages from the original Croatian. It is considered as the first widely translated Croatian text and an example of a deeply intimate and aesthetically valuable confessional letter.[14][15]

Besides being one of the most important military figures of the 17th centuryCroatia, Zrinski is also known for his literary works. Along with his wifeKatarina, brotherMiklós Zrínyi (although Miklós wrote in Hungarian and Latin) and brother-in-lawFran Krsto Frankopan he contributed greatly to 17th-century Croatian poetry.

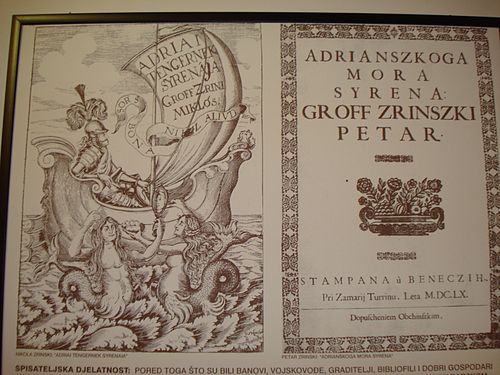

He published a translation of his brother's workAdrianskoga mora sirena [hr] (Syren of the Adriatic Sea) in 1660, to which he contributed his own verses and poetic ideas.[16]

Ragusan poetVladislav Menčetić dedicated his 1665 epic poemTrublja Slovinska to Petar Zrinski, where he was elevated as the saviour of Christendom against the Ottoman Empire.[17] In a similar way, historianJohannes Lucius dedicated the map ofIllyria "Illyricum hodiernum" within his work "De Regno Dalmatiae et Croatia" (1668; On the Kingdom of Dalmatia and Croatia) to him.[18]

The bones of Zrinski and Frankopan were found in Austria in 1907 and brought to Zagreb in 1919, where they were reburied in theZagreb Cathedral.[19]

Zrinski and Frankopan are still widely regarded as national heroes in Croatia as well as Hungary. Their portraits were depicted on theobverse of the Croatian 5kuna banknote, issued in 1993 and 2001.[20]

| Preceded by | Ban of Croatia 1665–1670 | Succeeded by |