The earliest known usage of the nameUkraine (Ukrainian:Україна,romanized: Ukraina[ʊkrɐˈjinɐ]ⓘ,Вкраїна,romanized:Vkraina[u̯krɐˈjinɐ];Old East Slavic:Ѹкраина/Ꙋкраина,romanized: Ukraina[uˈkrɑjinɑ]) appears in theHypatian Codex ofc. 1425 under the year 1187 in reference to a part of the territory ofKievan Rus'.[1][2]The use of "the Ukraine" has been officially deprecated by theUkrainian government and many English-language media publications.[3][4][5]

Ukraine is the official full name of the country, as stated inits declaration of independence andits constitution; there is no official alternative long name. From 1922 until 1991,Ukraine was the informal name of theUkrainian Soviet Socialist Republic within theSoviet Union (annexed by Germany asReichskommissariat Ukraine during 1941–1944). After theRussian Revolution in 1917–1921, there were the short-livedUkrainian People's Republic andUkrainian State,recognized in early 1918 as consisting of nine governorates of the formerRussian Empire (withoutTaurida'sCrimean Peninsula), plusChelm and the southern part ofGrodno Governorate.[6]

Although the exact meaning of the wordukraïna orukrajina as a whole is disputed, there is agreement thatkrajina is derived from theProto-Indo-European root*krei, meaning 'to cut', with 'edge' as a secondary meaning.[7] TheProto-Slavic word*krajь generally meant 'edge',[8] related to the verb*krojiti 'to cut (out)',[9] in the sense of 'division', either 'at the edge, division line', or 'a division, region'.[10] InOld Church Slavonic,krai has been attested with the meanings of 'edge, end, shore',[8] whileChurch Slavonicкроити (kroiti),краяти (krajati) could mean 'the land someone carved out for themselves' according to Hryhoriy Pivtorak (2001).[10] Derivatives in modern Slavic languages include variations ofkraj orkrai in a wide array of senses, such as 'edge, country, land, end, region, bank, shore, side, rim, piece (of wood), area'.[11]

Originally, the wordѹкра́ина (вкра́ина), from which the proper noun has been derived, formed in particular from the root-краи- (krai) and the prefixѹ-/в-[a] that later merged with the root due tometanalysis.

The ambiguity occurs due to thepolysemous nature of the root край, as it may mean either 'a boundary/edge of a certain area' or 'an area defined by certain boundaries',[13][14][circular reference] nevertheless both meanings allow for the formation of a valid toponym. For instance, the country nameDanmark is a composition of 'Danish' + 'boundary'.[15][16][circular reference]

The oldest recorded mention of the wordukraina is found in theKievan Chronicle under the year 1187,[2] as preserved in theHypatian Codex writtenc. 1425 in anOld East Slavic variety ofChurch Slavonic.[7] The passage narrates the death ofVolodimer Glebovich [uk;ru;pl],prince of Pereyaslavl'[7] (r. 1169–1187):[b]

ѡ нем же Ѹкраина много постона.[1] (ō nem zhe Ukraina mnogo postona).

"The frontier (Ukraina) mourned a great deal for him." (Lisa L. Heinrich, 1977)[b]

"Theukraïna groaned with grief for him." (Paul R. Magocsi, 2010)[7]

In context,Ukraina referred to the territory of thePrincipality of Pereyaslavl,[b][2] which was located betweenKievan Rus' heartland in theMiddle Dnieper region to the west, and thePontic–Caspian steppe to the southeast,[18] which the Rus' chronicles customarily referred to as "the land of thePolovtsi".[c]Ukraine came to mean 'steppe frontier' or 'steppe borderland' in the Ukrainian, Polish and Russian languages thereafter.[2]

The next mention ofukraina in the sameKievan Chronicle occurssub anno 1189,[7] which narrates how a certain Rostislav Berladnichich was invited by some, but not all, "men of Galich" (modernHalych), to take power in thePrincipality of Galicia:[21]

еха и Смоленьска в борзѣ и приѣхавшю же емоу ко Оукраинѣ Галичькои и взя два города Галичькъıи и отолѣ поіде к Галичю.[1]

"And he went in haste from Smolensk, and when he had come to the Galičan frontier," (ukraině Galichĭkoi) "he captured two Galičan cities. And from there he went to [the city of] Galič (...)." (Lisa L. Heinrich, 1977)[21]

Serhii Plokhy (2015, 2021) connected the 1189 mention to that of 1187, stating that both referred to the same region: "1187–1189 A Kyivan chronicler first uses the wordUkraine to describe the steppe borderland from Pereiaslav in the east to Galicia in the west."[22]

TheKievan Chronicle and subsequentGalician–Volhynian Chronicle in the Hypatian Codex mentionukraina again under the years 1189, 1213, 1280, and in 1282, where it is applied in various contexts.[7] In these decades, and the following centuries until the end of the Middle Ages, this term was applied to fortified borderlands of different principalities of Rus' without a specific geographic fixation:Halych-Volhynia,[7][23] the(Western) Buh region,[7]Pskov,[7][23]Polatsk,[7]Ryazan etc.[23]: 183 [24] According toSerhii Plokhy (2006), "theMuscovites referred to their steppe borderland as 'Ukraine', while reserving different names for areas bordering on the settled territories of theGrand Duchy of Lithuania and theKingdom of Poland".[2]

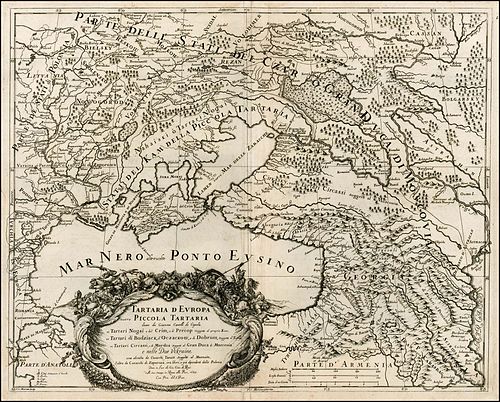

TheRadziwiłł map of 1613 (formal titleMagni Ducatus Lithuaniae; originally published in 1603[25]) was the first map to indicate the terms "Ukraine" and "Cossacks".[26] In the mid-17th century, Franco-Polish cartographerGuillaume Le Vasseur de Beauplan, who had spent the 1630s as a military engineer and architect designing and building fortifications in the region, played a significant role in popularisingUkraine as a name and a concept to a broader Western European audience, both through his maps and his writings.[27] His 1648General Map of Ukraine was titled in LatinDelineatio Generalis Camporum Desertorum vulgo Ukraina. Cum adjacentibus Provinciis ("General Map of theWild Fields, in common speech Ukraine. With adjacent Provinces"), thereby 'using the term "Ukraine" to denote all the provinces of the Kingdom of Poland that bordered on the uninhabited steppe areas (campus desertorum)'.[28][29] Beauplan's French-language publication of the second edition of theDescription of Ukraine (Description d'Ukranie, the first edition dates from 1651[30]) definedUkraine as "several provinces of the Kingdom of Poland lying between the borders of Muscovy and the frontiers of Transylvania".[28] This book became wildly popular in Western Europe, and was translated into Latin, Dutch, Spanish and English in the 1660s to 1680s, and reprinted numerous times throughout the rest of the 17th century and the entire 18th century.[28] On another map,[which?] published inAmsterdam in 1645, the sparsely inhabited region to the north of theAzov sea is called Okraina and is characterized to the proximity to the Dikoye pole (Wild Fields), posing a constant threat of raids of Turkic nomads (Crimean Tatars and theNogai Horde).[citation needed]

By the 17th century,Ukraine was sometimes used to define various other, non-steppe borderlands, but the word received more commonly-used and eventually fixed meanings in the second half of the 17th century.[27] After the south-western lands of former Rus' were subordinated to thePolish Crown in 1569, the territory from easternPodillia toZaporizhia got the unofficial name Ukraina due to its border function to the nomadicTatar world in the south.[32] A 1580 royal decree byStefan Batory 'made mention of Ruthenian, Kyivan, Volhynian, Podolian, and Bratslavian Ukraine'.[2]The Polish chroniclerSamuel Grądzki [pl] (died 1672), who wrote about theKhmelnytsky Uprising in 1660, explained the wordUkraina as the land located at the edge of thePolish kingdom.[d] Thus, in the course of the 16th–18th centuries Ukraine became a concrete regional name among other historic regions such asPodillia,Severia, orVolhynia. It was used for the middleDnieper River territory controlled by theCossacks.[23]: 184 [24] The people of Ukraina were called Ukrainians (українці,ukraintsi, orукраїнники,ukrainnyky).[34]

Later, the term Ukraine was used for theCossack Hetmanate lands on both sides of the Dnieper, although it didn't become the official name of the state.[24][35] Nevertheless, in diplomatic correspondence between the Zaporozhian Host and the tsar of Muscovy, Cossack officials increasingly used the term "Ukraine" to denote the Cossack Hetmanate ever sinceBohdan Khmelnytsky's leadership.[36] A May 1660 set of negotiation instructions written by hetmanYurii Khmelnytsky defined "Ukraine" as the territory controlled by the Cossack state according to theTreaty of Zboriv (1649), thus making it a political rather than geographic term.[36] The scope of this Cossack political concept of Ukraine was remarkably different from that popularised by Beauplan (who was influenced by Polish traditions) around the same time; Beauplan'sUkrainie was first and foremost a set of voivodeships controlled by the Kingdom of Poland, characterised by their juxtaposition to the steppes as opposed to the rest of Poland.[36]

TheCossack Hetmanate of theRight Bank was called the "Ukrainian State" (Ukrainskie Panstwo) in the 1672Treaty of Buchach between the Ottoman Empire and Poland.[37][38] The Ottomans used the term "Country of Ukraine" (Ukrayna memleketi).[39]

From the 18th century on, Ukraine became known in theRussian Empire by the geographic termLittle Russia.[23]: 183–184 In the 1830s,Mykola Kostomarov and hisBrotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius in Kyiv started to use the nameUkrainians.[citation needed] It was also taken up byVolodymyr Antonovych and theKhlopomany ('peasant-lovers'), former Polish gentry in Eastern Ukraine, and later by theUkrainophiles inHalychyna, includingIvan Franko. The evolution of the meaning became particularly obvious at the end of the 19th century.[23]: 186 The term is also mentioned by the Russian scientist and traveler of Ukrainian originNicholas Miklouho-Maclay (1846–1888). At the turn of the 20th century the term Ukraine became independent and self-sufficient, pushing aside regional self-definitions.[23]: 186 In the course of the political struggle between the Little Russian and the Ukrainian identities, it challenged the traditional term Little Russia (Russian:Малороссия,romanized: Malorossiia) and ultimately defeated it in the 1920s during theBolshevik policy ofKorenization andUkrainization.[40][41][page needed]

Since the first known usage in 1187, and almost until the 18th century, in written sources, this word was used in the meaning of "border lands", without reference to any particular region with clear borders, including far beyond the territory of modern Ukraine. The generally accepted and frequently used meaning of the word as "borderland" has increasingly been challenged by revision, motivated by self-asserting of identity.[42]

The etymology of the word Ukraine is seen this way in most etymological dictionaries,[citation needed] such asMax Vasmer's etymological dictionary of Russian;[43]Orest Subtelny,[44]Paul Magocsi,[45]Omeljan Pritsak,[46]Mykhailo Hrushevskyi,[47]Ivan Ohiyenko,[48]Petro Tolochko[49] and others. It is supported byJaroslav Rudnyckyj in theEncyclopedia of Ukraine[50] and the Etymological dictionary of theUkrainian language (based on that of Vasmer).[51]

Ukrainian scholars and specialists in Ukrainian and Slavic philology have interpreted the termukraina in the sense of "region, principality, country",[52] "province", or "the land around" or "the land pertaining to" a given centre.[53][54]

Linguist Hryhoriy Pivtorak (2001) argues that there is a difference between the two terms україна (Ukraina, "territory") and окраїна (okraina, "borderland"). Both are derived from the rootkrai, meaning "border, edge, end, margin, region, side, rim" but with a difference in preposition,U (ѹ)) meaning "at" vs.o (о) meaning "about, around"; *ukrai and *ukraina would then mean "aseparated land parcel, aseparate part of a tribe's territory". Lands that became part of theGrand Duchy of Lithuania (Chernihiv Principality,Siversk Principality,Kyiv Principality,Pereyaslavl Principality and most ofVolyn Principality) were sometimes called Lithuanian Ukraina, while lands that became part of Poland (Halych Principality and part of Volyn Principality) were called Polish Ukraina. Pivtorak argues thatUkraine had been used as a term for their own territory by theUkrainian Cossacks of theZaporozhian Sich since the 16th century, and that the conflation withokraina "borderlands" was a creation of tsarist Russia.[e] Russian scholars contest this.[citation needed]

Below are the names of the Ukrainian states throughout the 20th century:

Ukraine is one of a few English country names traditionally used with thedefinite articlethe.[3] Use of the article was standard before Ukrainian independence, but has decreased since the 1990s.[4][5][59] For example, theAssociated Press dropped the article "the" on 3 December 1991.[5] Use of the definite article was criticised as suggesting a non-sovereign territory, much like "the Lebanon" referred to the region before its independence, or as one might refer to "the Midwest", a region of the United States.[60][61][62][f]

In 1993, the Ukrainian government explicitly requested that, in linguistic agreement with countries and not regions,[65] the Russianprepositionв,v, be used instead ofна,na,[66] and in 2012, the Ukrainian embassy in London further stated that it is politically and grammatically incorrect to use a definite article withUkraine.[3] Use ofUkraine without the definite article has since become commonplace in journalism and diplomacy (examples are the style guides ofThe Guardian[67] andThe Times[68]).

In theUkrainian language bothv Ukraini (with the prepositionv - "in") andna Ukraini (with the prepositionna - "on") have been used, although the prepositionv is used officially and is more frequent in everyday speech.[citation needed] Modern linguistic prescription inRussian dictates usage ofna,[69] while earlier official Russian language have sometimes used 'v',[70] just like authors foundational to Russian national identity.[71] Similar to the definite article issue in English usage, use ofna rather thanv has been seen as suggesting non-sovereignty. Whilev expresses "in" with a connotation of "into, in the interior",na expresses "in" with the connotation of "on, onto" a boundary (Pivtorak citesv misti "in the city" vs.na seli "in the village", viewed as "outside the city"). Pivtorak notes that both Ukrainian literature and folk song uses both prepositions with the nameUkraina (na Ukraini andv Ukraini), but argues that onlyv Ukraini should be used to refer to the sovereign state established in 1991.[10] The insistence onv appears to be a modern sensibility,[according to whom?] as even authors foundational to Ukrainian national identity used both prepositions interchangeably, e.g.T. Shevchenko within the single poemV Kazemati (1847).[72][non-primary source needed]

The prepositionna continues to be used with Ukraine in theWest Slavic languages (Polish,Czech,Slovak), while theSouth Slavic languages (Bulgarian,Serbo-Croatian,Slovene) usev exclusively.[citation needed]

Among the western European languages, there is inter-language variation (and even sometimes intra-language variation) in the phonetic vowel quality of theai ofUkraine, and its written expression.[citation needed] It is variously:

In Ukrainian itself, there is a "euphony rule" sometimes used in poetry and music which changes the letter У (U) to В (V) at the beginning of a word when the preceding word ends with a vowel or a diphthong. When applied to the name Україна (Ukraina), this can produce the form Вкраїна (Vkraina), as in song lyric Най Вкраїна вся радіє (Nai Vkraina vsia radiie, "Let all Ukraine rejoice!").[73]

As of December 3, the Associated Press changed its style, alerting its editors, reporters and all who use the news service to the fact that the name of the Ukrainian republic would henceforth be written as simply "Ukraine"

В 1993 году по требованию Правительства Украины нормативными следовало признать варианты в Украину (и соответственно из Украины). Тем самым, по мнению Правительства Украины, разрывалась не устраивающая его этимологическая связь конструкций на Украину и на окраину. Украина как бы получала лингвистическое подтверждение своего статуса суверенного государства, поскольку названия государств, а не регионов оформляются в русской традиции с помощью предлогов в (во) и из...

The dictionary definition ofUkraine at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition ofUkraine at Wiktionary