Kouang-Tchéou-Wan 廣州灣 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1898–1945 | |||||||||

Flag | |||||||||

| |||||||||

Location of Kwangchow Wan and French Indochina | |||||||||

| Status | Leased territory ofFrance | ||||||||

| Capital | Fort Bayard | ||||||||

| Common languages |

| ||||||||

| Historical era | New Imperialism | ||||||||

• French occupation | April 22, 1898 | ||||||||

• Leased by France | May 29, 1898 | ||||||||

• Administered byFrench Indochina | January 5, 1900 | ||||||||

• Occupied byJapan | February 21, 1943 | ||||||||

• Returned byFrance | August 18, 1945 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1,300 km2 (500 sq mi) | |||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1911 | 189,000 | ||||||||

• 1935 | 209,000 | ||||||||

| Currency | piaster | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Leased Territory of Guangzhouwan | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 廣州灣 | ||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 广州湾 | ||||||||||||||

| CantoneseYale | gwóng dzàu wāan | ||||||||||||||

| Jyutping | Gwong2 Zau1 Waan1 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Guangzhou Bay | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| French name | |||||||||||||||

| French | Kouang-Tchéou-Wan | ||||||||||||||

TheLeased Territory of Guangzhouwan, officially theTerritoire de Kouang-Tchéou-Wan and historically known in English asKwangchowan orKwangchow Wan, was a coastal territory ofZhanjiang,China leased to France and administered byFrench Indochina.[1] The capital of the territory was Fort Bayard, nowZhanjiang.[nb 1]

The Japanese occupied the territory in February 1943; following Japanese surrender in 1945, France formally relinquished the territory to theRepublic of China. The territory did not experience the rapid growth in population that other parts of coastal China experienced, rising from 189,000 in the early 20th century[2] to just 209,000 in 1935.[3]

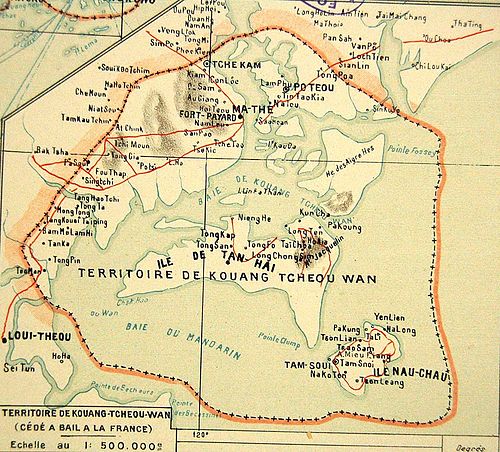

The leased territory was situated on the east side of theLeizhou (Luichow) Peninsula (French:Péninsule de Leitcheou), near Guangzhou, around a bay then calledKwangchowan, now called thePort of Zhanjiang. The bay forms the estuary of the Ma-The River (French:Rivière Ma-The,Chinese:麻斜河;pinyin:Máxié hé), now known as the Zhanjiang Waterway (Chinese:湛江水道;pinyin:Zhànjiāng shuǐdào)[4] which is navigable as far as 19 kilometers (12 mi) inland even by large warships.

The territory leased to France included the islands lying in the bay, which enclosed an area 29 km long by 10 km wide and a minimum water depth of 10 meters (5.5 fathoms). The islands were then renowned for their admirable natural defenses, the main island beingÎle de Tan-Hai. On the smallerÎle Nau-Chau farther to the southeast, a lighthouse was constructed. Another island of significant size isÎle des Aigrettes [fr] located to the northeast.

The limits of the territory inland were fixed in November 1899; on the left bank of the Ma-the, France gained fromGaozhou prefecture (Kow Chow Fu) a strip of territory 18 kilometers (11 mi) by 10 kilometers (6.2 mi), and on the right bank a strip 24 kilometers (15 mi) by 18 kilometers (11 mi) fromLeizhou prefecture (Luichowfu).[2] Its total land area consisted 1,300 km2 (500 sq mi).[3]

Kwangchowan was leased to the French for 99 years according to the Treaty of May 29, 1898, ratified by China on January 5, 1900, during the "scramble for concessions". The colony was described as "commercially unimportant but strategically located"; most of France's energies went into their administration of the mainland of French Indochina, and their main concern in China was the protection of Roman Catholic missionaries, rather than the promotion of trade.[1] Kwangchow Wan, while not a constituent part of Indochina, was effectively placed under the authority of the FrenchResident Superior inTonkin (itself under the Governor-General of French Indochina, also in Hanoi); the French Resident was represented locally by Administrators.[5] In addition to the territory acquired, France was given the right to connect the bay by rail with the city and harbor situated on the west side of the peninsula; however when they attempted to take possession of the land to build the railway, forces of the provincial government offered armed resistance. As a result, France demanded and obtained exclusive mining rights in the three adjoining prefectures.[2] The return of the leased territory to China was promised after theFirst World War by the French at theWashington Naval Conference of 1921–1922,[6] but that promise was not fulfilled until 1945, by which time the territory had already ceased to be under French rule.

By 1931, the population of Kwangchowan had reached 206,000, giving the colony a population density of 245 persons per km2 (630 per square mile); virtually all Chinese, and only 266 French citizens and four other Europeans were recorded as living there.[3] Industries included shipping and coal mining.[5] The port was also popular with smugglers; prior to the 1928 cancellation of the American ban on the export of commercial airplanes, Kwangchow Wan was also used as a stop for Cantonese smugglers transporting military aircraft purchased in Manila to China,[7] and American records mention at least one drug smuggler who picked up opium andpaper sons (Chinese American emigrants circumventing theChinese Exclusion Act) to smuggle into the United States.[8]

As an adjunct of French Indochina, Kwangchow Wan generally endured the same fate as the rest of the Indochina colony during World War II. Even before the signing of the August 30, 1940 accord with Japan in which France recognized the “privileged status of Japanese interests in the Far East” and which constituted the first step of the Japanese military occupation of Indochina, a small detachment of Japanese marines had landed at Fort Bayard without opposition in early July and set up a control and observation post in the harbor.[9] However, as in the rest of French Indochina, the civilian administration of the territory was to remain in the hands of officials ofVichy France following theFall of France; in November 1941, Governor-GeneralJean Decoux, newly appointed by MarshalPhilippe Pétain, made an official visit to Kwangchow Wan.[10]

In mid-February 1943, the Japanese, after having informed the Vichy government that they needed to strengthen the defenses of Kwangchow Wan, unilaterally landed more troops and occupied the airport and all other strategic locations in the Territory. From then on, Kwangchow Wan wasde facto under full military Japanese occupation and the French civilian administration was gradually reduced to a mere façade. The Administrator resigned in disgust and Adrien Roques, a local pro-Vichy militant, was appointed to replace him.[11] In May of the same year, Roques signed a convention with the local Japanese military authorities in which the French authorities promised to cooperate fully with the Japanese. On March 10, 1945, the Japanese, following up on theirsudden attack on French garrisons throughout Indochina the night before, disarmed and imprisoned the small French colonial garrison in Fort Bayard.[12] Just prior to the Japanese surrender, Chinese forces were prepared to launch a large-scale assault on Kwangchow Wan; however, due to the end of the war, the assault never materialized.[13] While the Japanese were still occupying Kwangchow Wan following the surrender, a French diplomat from theProvisional Government of the French Republic and Kuo Chang Wu, Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of China, signed theConvention between the Provisional Government of the French Republic and the National Government of China for the retrocession of the Leased Territory of Kouang-Tchéou-Wan. Almost immediately after the last Japanese occupation troops had left the territory in late September, representatives of the French and the Chinese governments went to Fort Bayard to proceed to the transfer of authority; the French flag was lowered for the last time on November 20, 1945.[14]

During theJapanese occupation of Hong Kong, Kwangchowan was often used as a stopover on an escape route for civilians fleeing Hainan and Hong Kong for Thailand,North America and Free China;Patrick Yu, a prominent trial lawyer, recalled in his memoirs how a Japanese military officer helped him escape in this way.[15] However, the escape route was closed when the Japanese occupied the area in February 1943.[16]

The territory was formally returned to theRepublic of China on August 18, 1945 after a meeting[clarification needed] between the French and Chinese.[17]

![[icon]](/image.pl?url=http%3a%2f%2fen.wikipedia.org%2f%2fupload.wikimedia.org%2fwikipedia%2fcommons%2fthumb%2f1%2f1c%2fWiki_letter_w_cropped.svg%2f20px-Wiki_letter_w_cropped.svg.png&f=jpg&w=240) | This sectionneeds expansion. You can help byadding to it.(June 2008) |

A French language school (École Franco-Chinoise de Kouang-Tchéou-Wan) and French bank (Bank of Indochina), among other institutions were set up;[18]some such as the Church of St. Victor are extant.[19]