Colonies in antiquity were post-Iron Agecity-states founded from a mother-city ormetropolis rather than from a territory-at-large. Bonds between acolony and its metropolis often remained close, and took specific forms during the period ofclassical antiquity.[1]Generally, colonies founded by the ancientPhoenicians,Carthage,Rome,Alexander the Great and hissuccessors remained tied to their metropolis, thoughGreek colonies of theArchaic andClassical eras were sovereign and self-governing from their inception. While earlier Greek colonies were often founded to solvesocial unrest in the mother-city by expelling a part of the population,Hellenistic,Roman,Carthaginian, andHan Chinese colonies served as centres fortrade (entrepôts), expansion andempire-building.

Egyptian settlement and colonisation is attested from about 3200 BC onward, all over the area of southernCanaan, by almost every type of artifact: architecture (fortifications, embankments and buildings), pottery, vessels, tools, weapons, seals, etc.[2][3]Narmer hadEgyptian pottery produced inCanaan and exported back toEgypt,[4] from regions such asArad,En Besor,Rafiah, andTel Erani.[4] An area of permanent settlement may have been administered fromTell es-Sakan, which is the largest Egyptian settlement in the region.[5] An Early Bronze Age brewery belonging to an Egyptian settlement was found inTel Aviv.[6]Shipbuilding was known to theancient Egyptians as early as 3000 BC, and perhaps earlier. TheArchaeological Institute of America reports[7] that the earliest dated ship — dating to 3000 BC[8] – may have belonged to the PharaohAha.[8]

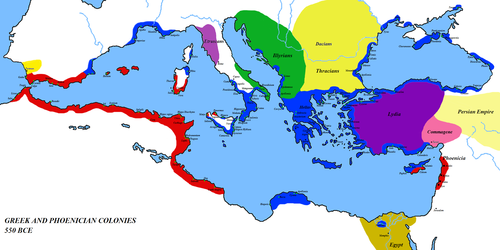

ThePhoenicians were the majortradingpower in theMediterranean in the early part of thefirst millennium BC. They had trading contacts inEgypt andGreece, and established colonies as far west as modernSpain, at Gadir (modernCádiz), and modernMorocco, atTingis andMogador. From Spain and Morocco, the Phoenicians controlled access to theAtlantic Ocean and thetrade routes toBritain andSenegal.

The most famous and successful of Phoenician colonies was founded by settlers fromTyre in 814–813 BC and called Kart-Hadasht (Qart-ḥadašt,[9] literally "New Town"[10]), known in English asCarthage. TheCarthaginians later founded their own colonies in the western Mediterranean, notably a colony in southeast Spain,Carthago Nova, which was eventually conquered by their enemy,Rome.

According toMaría Eugenia Aubet, Professor of Archaeology at thePompeu Fabra University, Barcelona:

The earliest presence of Phoenician material in the West is documented within the precinct of the ancient city ofHuelva, Spain... The high proportion of Phoenician pottery among the new material found in 1997 in the Plaza de las Monjas in Huelva argues in favour, not of a few first sporadic contacts in the zone, but of a regular presence of Phoenician people from the start of the ninth century BC. The recent radiocarbon dates from the earliest levels in Carthage situate the founding of this Tyrian colony in the years 835–800 cal BC, which coincides with the dates handed down by Flavius Josephus and Timeus for the founding of the city.[11]

The nature of the origins ofDʿmt (founded c. 800 BCE around Ethiopia'sTigray Region) regarding the role played by Sabaeans fromSheba in South Arabia continues to be debated by historians.[12][13]: 90–94 Evidence of strong Sabaean influence includesSabaic inscriptions and Sabaean temples. As of 2017, scholars ofSouth Arabian archaeology andepigraphy tended to favour a migration and/or colonisation, while scholars ofAfrican archaeology tended to stress an indigenous origin.[14] However writing in 2025Alfredo González-Ruibal [es] said that "idea of colonisation as such has been discarded".[15]

In 2019,[16] Sabaean inscriptions were found inSomaliland andPuntland, as well as a Sabaean temple whose inscriptions say its construction was ordered by the admiral of Sheba's fleet. González-Ruibal said "we can perhaps discern two different models: a proper colonialist one along the northern Somali seaboard, with direct intervention of the state and aimed at the extraction of resources, and a diasporic model in the northern Horn, led by élites who soon mixed with local people, while maintaining ties with their ancestral homeland".[15]

InAncient Greece, a defeated people would sometimes found a colony, leaving their homes to escape the subjugation of a foreign enemy. Sometimes colonies formed as a result ofcivil disorder, where the losers in internecine battles left to form a new city elsewhere; sometimes they would form to relieve population pressure and thereby to avoid internal unrest; and also, as a result ofostracism. In most cases, however, colony founders aimed to establish trade relations with foreign countries and to further the wealth of the metropolis. Colonies were established inIonia andThrace as early as the 8th century BC.[17]

More than thirty Greek city-states had multiple colonies, dotted all across theMediterranean world. From the late 9th to the 5th century BC, the most active colony-founding city,Miletus of theIonian League, spawned more than 60 colonies[18] encompassing the shores of theBlack Sea in the east, theIberian Peninsula in the west,Magna Graecia (southern Italy) and several colonies on the Libyan coast of northernAfrica.[19]

Greeks founded two similar types of colony, theapoikía (ἀποικία from ἀπόapó “away from” + οἶκοςoîkos “home”, pl. ἀποικίαιapoikiai), an independent city-state, and theemporion (ἐμπόριov, pl. ἐμπόριαemporia), a trading colony.

Greek city-states began to establish colonies between 900[20] and 800 BC; the first two wereAl Mina on theSyrian coast and the Greek emporiumPithecusae atIschia in theBay of Naples, both established about 800 BC byEuboeans.[21]

Two new waves of colonists set out from Greece between theDark Ages and the start of theArchaic Period – the first in the early 8th century BC and the second in the 6th century. Population growth and cramped conditions at home seem an insufficient explanation, while the economic and political dynamics produced by the competition between the frequently leaderless Greek city-states – newly introduced as a concept and striving to expand their spheres of economic influence – better fits as their true incentive. By means of this Greek expansion, the use of coins flourished throughout theMediterranean Basin.

Influential Greek colonies in the western Mediterranean – many in present-day southern Italy — includedCyme;Rhegion byChalcis andZancle (c. 8th century);Syracuse byCorinth andTenea (c. 734 BC);Naxos by Chalcis (c. 734 BC);Massalia (Marseille, c. 598 BC) andAgathe, shortly after Massalia, byPhocaea;Hyele in Italy andEmporion inSpain by Phocaea and Massalia (c. 540 BC and early 6th century);Antipolis in France byAchaea;Alalia inCorsica by Phocaea and Massalia (c. 545 BC) andCyrene (Cyrenaica, Libya) byThera (762/61 and 632/31 BC).[22]

The Greeks alsocolonised theCrimea in theBlack Sea. The settlements they established there included the city ofChersonesos (modernSevastopol).[23] Another area with significant Greek colonies was the coast of ancientIllyria on theAdriatic Sea (e.g. Aspalathos, modernSplit, Croatia).

Cicero remarks on the extensive Greek colonization, noting that "Indeed it seems as if the lands of the barbarians had been bordered round with a Greek sea-coast."[24] Several formulae generally shaped the solemn and sacred occasions when a new colony set forth. If a Greek city decided to send out a colony, the citizenry almost invariably consulted anoracle, such as theOracle of Delphi, beforehand. Sometimes certain classes of citizens were called upon to take part in the enterprises; sometimes one son was chosen by lot from every house where there were several sons; and strangers expressing a desire to join were admitted. A person of distinction was selected to guide the emigrants and to make the necessary arrangements. It was usual to honor these founders as heroes after their death. Some of the sacred fire was taken from the public hearth in thePrytaneum, from which the fire on the public hearth of the new city was kindled. Just as each individual had his private shrines, so the new community maintained the worship of its chief domestic deities, the colony sending embassies and votive gifts to the mother-city's principal festivals for centuries afterwards.

After the conquests ofMacedonia andAlexander the Great, a further number ofHellenistic colonies were founded, ranging from Egypt to India.

By the 15th century BC, theMycenaeans had reachedRhodes,Crete andCyprus ( whereTeucer is said to have founded the first colony) and the shores ofAnatolia.[25][26] In addition, Greeks were settled inIonia andPontus.Miletus in Ionia was an ancient Greek city on the west coast of Anatolia, near the mouth of theMeander River. In the lateBronze Age (13th century BC), Miletus saw the arrival of theCarians,Luwian speakers from south central Anatolia. Later in that century, other Greeks arrived. The city at that time rebelled against theHittite Empire. After the fall of that empire, the city was destroyed in the 12th century BC and starting about 1000 BC was resettled extensively by Ionians.

Before the invasion fromPersia in the middle of the 6th century BC, Miletus was considered the greatest and wealthiest Greekpolis.[27][28] Over several centuries, numerous ancient Greek city-states were established on the coasts of Anatolia. Greeks beganWestern philosophy on the western coast of Anatolia (Pre-Socratic philosophy).[29]Thales,Anaximander,Anaximenes andDiogenes of Apollonia were among the renowned philosophers of theMilesian school.Heraclitus lived inEphesus another ancient Greek city[30][31] andAnaxagoras was fromClazomenae, a member of theIonian League. All theAncient Greek dialects were spoken in Anatolia in the various city states and thelist of ancient Greek theatres in Anatolia is one of the longest among all places the Greeks settled.

Greeks traditionally lived in the region ofPontus, on the south shores of the Black Sea and in thePontic Alps in northeasternAnatolia, the province of Kars in Caucasus, and also in Georgia. Those from southern Russia, Ukraine, and Crimea are often referred to as 'NorthernPontic Greeks', in contrast to those from 'South Pontus', which strictly speaking isPontus proper. Those from Georgia, northeastern Anatolia, and the ones who lived in present-day Armenia are often referred to as 'EasternPontic Greeks' or Caucasus Greeks. Many Greek-founded colonies are well known cities to this day.Sinope andTrabzon (Greek: ΤραπεζοῦςTrapezous), were founded byMilesian traders (756 BC) as well asSamsun,Rize andAmasra. Greek was the lingua franca of Anatolia from the conquests ofAlexander the Great up to the invasion of theSeljukTurks in the eleventh century AD.

During the Ptolemaic rule of Judea, large-scale Jewish settlement in Egypt commenced. The Ptolemies brought in Jewish soldiers along with their families, while other Jews migrated from Judea to Egypt likely for economic opportunities. Additionally, the Ptolemies established Jewish colonies in the cities of Cyrenaica (modern-day Libya).[32]

The relation between colony and mother-city (metropolis) was viewed[by whom?] as one of mutual affection. Differences were resolved peacefully whenever possible, war being seen as a last resort. (Note though that thePeloponnesian War of 431–404 BC broke out partly due to a dispute betweenCorinth and her colonyCorcyra.)

The charter of foundation contained general provisions for the arrangement of the affairs of the colony, and also some special enactments. A colony would usually adopt the constitution of the mother-city, but the new city remained politically independent. The "holy fire" of themetropolis was preserved in a special place to remind people of the common ties. If the colony sent out a fresh colony on its own account, the mother-city was generally consulted, or was at least asked to furnish a leader. Frequently the colonies, declaring their commitment to the various metropolitic alliances formed in the Greek mainland and for religious reasons, would pay tribute in religious centres such as Delphi,Olympia, orDelos.[33]

Thecleruchs (κληροῦχοι,klêrouchoi) formed a special class of Greek colonists, each being assigned an individual plot of land (κλῆρος,klêros). The trade factories set up in foreign countries, such asNaucratis in Egypt, were somewhat different from ordinary colonies, with the members retaining the right of domicile in their own homeland and confining themselves to their own quarter in the foreign city.

It was an old custom inancient Italy to send out colonies for the purpose of securing new conquests. TheRomans, having nostanding army, used to plant bodies of their own citizens in conquered towns as a kind of garrison. These bodies would consist partly ofRoman citizens, usually to the number of three hundred and partly of members of theLatin League in larger numbers. One third of the conquered territory was taken for the settlers. Thecoloniae civium Romanorum (colonies of Roman citizens) were specially intended to secure the two coasts of Italy, and were hence calledcoloniae maritimae. The far more numerouscoloniae Latinae served the same purpose for the mainland, but they were also inhabited by Latins and much more populated.

The duty of leading the colonists and founding the settlement was entrusted to a commission usually consisting of three members. These men continued to stand in the relation ofpatrons (patroni) to the colony after its foundation. The colonists entered the conquered city in military array, preceded by banners, and the foundation was celebrated with special solemnities. The coloniae were free from taxes, and had their ownconstitution, a copy of the Roman, electing from their own body theirSenate and other officers of State. To this constitution the original inhabitants had to submit. Thecoloniae civium Romanorum retainedRoman citizenship, and were free from military service, their position as outposts being regarded as an equivalent. The members of thecoloniae Latinae served among thesocii, the allies, and possessed the so-calledius Latinum or Latinitas. This secured to them the right of acquiring property, the concept ofcommercium, and the right of settlement in Rome, and under certain conditions the power of becoming Roman citizens; though in course of time these rights underwent many limitations.

From the time of theGracchi the colonies lost their military character. Colonization came to be regarded as a means of providing for the poorest class of theRoman Plebs. After the time ofSulla it was adopted as a way of granting land to veteran soldiers. The right of founding colonies passed into the hands of theRoman emperors during thePrincipate, who used it mainly in theprovinces for the exclusive purpose of establishing military settlements, partly with the old idea of securingconquered territory. It was only in exceptional cases that the provincial colonies enjoyed the immunity from taxation which was granted to those in Italy.[34]

Imperial China during theHan dynasty (202 BC–220 AD) extended its rule over what is now much ofChina proper as well asInner Mongolia,northern Vietnam,northern Korea, theHexi Corridor ofGansu, and theTarim Basin region ofXinjiang on the easternmost fringes of Central Asia. After the nomadic MongolicXiongnu ruler Hunye (渾邪) wasdefeated byHuo Qubing in 121 BC, settlers from various regions of China under the rule ofEmperor Wu of Han colonized the Hexi Corridor andOrdos Plateau.[35]Tuntian, self-sustaining agricultural military garrisons, were established in frontier outposts to secure the massive territorial gains andSilk Road trade routes leading into Central Asia.[36] Emperor Wu oversaw theHan conquest of Nanyue in 111 BC, bringing areas ofGuangdong,Guangxi,Hainan Island, and northernVietnam under Han rule, and by 108 BC completed theHan conquest of Gojoseon in what is nowNorth Korea.[37] Han Chinese colonists in theXuantu andLelangcommanderies of northern Korea dealt with occasional raids by theGoguryeo andBuyeo kingdoms, but conducted largely peaceful trade relations with surroundingKorean peoples who in turn became heavily influenced byChinese culture.[38]

In 37 AD theEastern Han generalMa Yuan sent Han Chinese to the northeastern frontier and settled defeatedQiang tribes within Han China'sTianshui Commandery andLongxi Commandery.[39] Ma pursued a similar policy in the south when he defeated theTrưng Sisters ofJiaozhi, in what is now modernnorthern Vietnam, resettling hundreds of Vietnamese into China'sJing Province in 43 AD, seizing theirsacred bronze drums as rival symbols of royal power, and reinstating Han authorityand laws over Jiaozhi.[40] HistorianRafe de Crespigny remarks that this was a "brief but effective campaign of colonisation and control", before the general returned north in 44 AD.[40]

Cao Song, an Eastern Han administrator ofDunhuang, had military colonies established in what is nowYiwu County nearHami in 119 AD. However, EmpressDeng Sui, regent for the youngEmperor Shang of Han, pursued a slow, cautious policy of settlement on the advice of Ban Yong, son ofBan Chao, as the Eastern Han Empire came into conflict with theJushi Kingdom, theShanshan and theirXiongnu allies located around theTaklamakan Desert in theWestern Regions.[41] In 127 AD Ban Yong was able to defeat theKarasahr in battle and colonies were established all the way toTurfan, but by the 150s AD the Han presence in the Western Regions began to wane.[42] Towards theend of the Han dynasty, chancellorCao Cao established agricultural military colonies for settling wartime refugees.[43] Cao Cao also established military colonies inAnhui province in 209 AD as a means to clearly demarcate a border between his realm and that of his political rivalSun Quan.[44]

...at their new location, colonists were expected to retain ties with their metropolis. A colony that sided with its metropolis's enemy in a war, for example was regarded as disloyal...

From the 8th century BC the coast of Thrace was colonised by Greeks.

{{cite book}}:ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)Robin Lane Fox examines the cultural connections made by Euboean adventurers in the 8th century