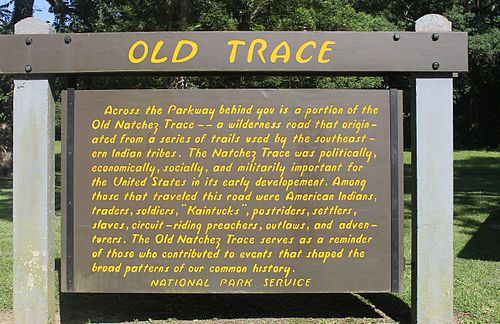

TheNatchez Trace, also known as theOld Natchez Trace, is a historic forest trail within theSoutheastern United States which extends roughly 440 miles (710 km) fromNashville, Tennessee, toNatchez, Mississippi, linking theCumberland,Tennessee, andMississippi rivers.

Native Americans created and used the trail for centuries. Early European and American explorers, traders, and immigrants used it in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. European Americans founded inns, also known as "stands", along the Trace to serve food and lodging to travelers. Most of these stands closed as travel shifted to steamboats on the Mississippi and other rivers. The heyday of the Trace began in the 1770s and ended in the 1820s; by the 1830s, the route was already in disrepair and its time as a major interregional commercial route had come to an end.[1]

Today, the path is commemorated by the 444-mile (715 km)Natchez Trace Parkway, which follows the approximate path of the Trace,[2] as well as the relatedNatchez Trace Trail. Parts of the original trail are still accessible, and somesegments are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Largely following a geologic ridge line, prehistoric animals followed the dry ground of the Trace to distant grazing lands, thesalt licks of today'sMiddle Tennessee, and to the Mississippi River. Native Americans used manyearly footpaths created by the foraging ofbison,deer, and other largegame that could break paths through the dense undergrowth. In the case of the Trace, bison traveled north to find salt licks in the Nashville area.[3]

After Native Americans began to settle the land, theyblazed the trail and improved it further until it became a relatively well-established path. Numerousprehistoricindigenous settlements in Mississippi were established along the Natchez Trace. Among them were the 2,000-year-oldPharr Mounds of the MiddleWoodland period, located near present-dayTupelo, Mississippi.

The first recorded European explorer to travel the Trace in its entirety was an unnamedFrenchman in 1742, who wrote of the trail and its "miserable conditions". Early European explorers depended on the assistance of Native American guides to go through this territory — specifically, theChoctaw andChickasaw who occupied the region. These tribes and earlier prehistoric peoples, collectively known as theMississippian culture, had long used the Trace for trade. The Chickasaw leader, ChiefPiomingo, made use of the trail so often that it became known asPiominko's Path during his lifetime.[4] Another early common name wasTrail to the Chickasaw Nation.[5]: 42

According to Methodist circuit preacher J. G. Jones, who traveled the lower Mississippi region for many years as part of his work, "Besides the water route, following the eastern tributaries of the Mississippi River to the Father of Waters and floating down to the point of debarkation, there were three land routes—mere horse-paths—opened through the Indian country to Natchez and other settlements on the Lower Mississippi. These were maintained by the Government for mail routes, by treaty stipulations with the Indian tribes. The first began at Nashville, and crossed theTennessee River atColbert's ferry, below theMuscle Shoals; thence through the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nation to theGrindstone Ford onBayou Pierre, ending at Natchez andFort Adams. The second began atKnoxville, and passed through the Cherokee Nation by way of theTellico andTombigbee rivers to Natchez. The third was from theOconee settlements, in Georgia, through the Creek Nation across theAlabama River in the direction ofSt. Steven's, on westwardly to Natchez. The traders of the Upper Mississippi River and its tributaries, who brought down their produce in flatboats, were accustomed to return on foot or horseback by the first route—called the Nashville and Natchez trace—and hence it became best known."[6]

Even before the 1803Louisiana Purchase, PresidentThomas Jefferson wanted to connect the distant Mississippi frontier to other settled areas of the United States. To foster communication with what was then called the Southwest, he directed the construction of a postal road betweenDaniel Boone'sWilderness Road (the southern branch of the road ended at Nashville) and the Mississippi River.

The U.S. signed treaties with theChickasaw andChoctaw tribes to maintain peace asEuropean Americans entered the area in greater numbers. In 1801, theUnited States Army began trailblazing along the Trace, performing major work to prepare it as a thoroughfare. The work was done by soldiers reassigned from Tennessee and later by civilian contractors. Jefferson called it the "Columbian Highway" to emphasize American sovereignty in the area. The people who used it, however, dubbed the road "The Devil's Backbone" due to its remoteness, rough conditions, and the frequently encounteredhighwaymen found along the new road.[2]Aaron Burr wrote to his daughter, that the "'road...you will see laid down...on the map...as having been cut by the order of the minister of war[,]...is imaginary; there is no such road.' The region between Washington, Mississippi, and the Choctaw domain was, Burr reported, 'a vile country, destitute of springs or of running water—think of drinking the nasty puddle water, covered with green scum, and full ofanimaculae—bah! … [H]ow glad I was to get [into the high country,] all fine, transparent, lively streams, and itself [the Tennessee] a clear, beautiful, magnificent river.'"[7]

By 1809, the trail was fully navigable by wagon, with the northward journey taking two to three weeks. Critical to the success of the Trace as a trade route was the development of inns andtrading posts, referred to at the time as "stands".[2]

Many early migrants in Tennessee and Mississippi settled along the Natchez Trace. Some of the most prominent wereWashington, Mississippi (the old capital of Mississippi); "Old"Greenville, Mississippi (whereAndrew Jackson marriedRachel Jackson in 1791);[8] andPort Gibson, Mississippi.[9] The Natchez Trace was used during theWar of 1812 and the ensuingCreek War, as soldiers under Major General Andrew Jackson's command traveled southward to subdue theRed Sticks and to defend the country against invasion by theBritish. Jackson most likely knew the road well from hiscareer as an interstate slave trader operating between Natchez and Nashville beginning in 1789.[10]

By 1817, the continued development ofMemphis (with its access to the Mississippi River) andJackson's Military Road (heading south from Nashville) formed more direct and faster routes toNew Orleans. Trade shifted to either of these routes along the east or west of the area, away from the Trace.[2] As authorWilliam C. Davis wrote in his bookA Way Through the Wilderness (1995), the Trace was "a victim of its own success" by encouraging development in the frontier area.

With the rise ofsteamboat culture on the Mississippi River after the invention of the steam engine, the Trace lost its importance as a national road, as goods could be moved more quickly, cheaply, and in greater quantity on the river.[2] Before the invention ofsteam power, the Mississippi River's south-flowing current was so strong that northbound return journeys generally had to be made over land.

Although many authors have written that the Trace disappeared back into the woods, much of it was used by people living nearby. Large sections of the Trace in Tennessee were converted to county roads for operation, and sections continue to be used today.

Though the Natchez Trace was briefly used as a major United States route, it served an essential function for years. The Trace was the only reliable land link between the eastern states and the trading ports of Mississippi andLouisiana. All sorts of people traveled down the Trace: itinerant preachers,highwaymen, traders, andpeddlers among them.[2] The road was most heavily used for mail in the 1810s, until about 1825.[11]

In those days the mail for the Southwest was carried on horseback along the trail. A rider left Nashville every Saturday night at 8 o'clock and was due in Natchez 10 days and four hours later. His equipment consisted of his sack mail, a half bushel of corn for his horse, a blanket and for announcing his arrival when neared a settlement a bugle. Sunday morning found thehorseman atGordon's Ferry onDuck River, 51 miles from Nashville.Then he rode 80 miles more toColbert's Ferry on theTennessee River before nightfall and there the Indians ferried him across. After a night's rest he started next morning for theChickasaw agency, 120 miles farther on, camping out in the canebrakes if he failed to reach there before dark. At the Chickasaw agency he made his first exchange of horses.Next was theChoctaw agency, 200 miles distant, and 100 miles beyond that point lay Natchez, the gateway to the great Southwest.

As part of the "Great Awakening" movement that swept the country in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the "spiritual development" along the Trace started from the Natchez end and moved northward. SeveralMethodist preachers began working acircuit along the Trace as early as 1800. By 1812 they claimed a membership of 1,067white Americans and 267African Americans.[12] The Methodists were soon joined in Natchez by otherProtestant denominations, includingBaptistmissionaries andPresbyterians.

The latter accompanied the migration of Scots-Irish and Scots into the frontier areas. Presbyterians and their frontier offshoot, theCumberland Presbyterians, were the most active of the three denominations in this country. They claimed converts among Native Americans. The Presbyterians started working from the south; the Cumberland Presbyterians worked from the north, as they had migrated to Tennessee from Kentucky.

As with the much-unsettled frontier, banditry regularly occurred along the Trace. Much of it centered around the river landingNatchez Under-The-Hill, as compared with the rest of the town atop the river bluff. Under-the-Hill, where barges andkeelboats put in with goods from northern ports, was a hotbed of gamblers, prostitutes, and drunken crew from the boats. Many of the rowdies, referred to as "Kaintucks", were rough Kentucky frontiersmen who operatedflatboats down the river.[2] They delivered goods to Natchez in exchange for cash and sought gambling contests in Natchez Under-the-Hill. They walked or rode horseback the 450 miles back up the Trace to Nashville. In 1810, an estimated 10,000 "Kaintucks" used the Trace annually to return to the north to start another river journey.[2]

Other dangers lurked on the Trace in the areas outside city boundaries. Highwaymen (such asJohn Murrell,Samuel Mason and theHarpe Brothers) terrorized travelers along the road. They operated large gangs of organizedbrigands in one of the first examples of land-basedorganized crime in the United States.[13][14]

Theinns, or stands, as they were called along the Natchez Trace, provided lodging for travelers from the 1790s to the 1840s. These stands furnished food and accommodations and contributed to the spread of news, information, and new ideas. The food was basic: corn in the form ofhominy was a staple, and bacon, biscuits, coffee with sugar, and whiskey were served. Lodging was normally on the floor; beds were available only to a few due to many travelers and cramped conditions. Some travelers chose to sleep outdoors or on the porches.[17]

Source:[21]

Meriwether Lewis, of theLewis and Clark Expedition fame, died while traveling on the Trace. Then serving as appointed governor of theLouisiana Territory, he was on his way to Washington, D.C., from his base in St. Louis, Missouri. Lewis stopped atGrinder's Stand (near current-dayHohenwald, Tennessee) for overnight shelter in October 1809. He was distraught over many issues, possibly affected by his use ofopium. He was believed by many to have committedsuicide there with a gun.[citation needed]

Some uncertainty persists as to whether it was suicide.[2] His mother believed he had been murdered, and rumors circulated about possible killers.Thomas Jefferson and Lewis's former partner,William Clark, accepted the report of suicide. Lewis was buried near the inn along the Trace.[22] In 1848, a Tennessee state commission erected a monument at the site.

On the bicentennial of Lewis's death (2009), the first national public memorial service honoring his life was held; it was also the last event of the Lewis and Clark Expedition Bicentennial.

{{cite book}}:ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)[2]