This package allows you to fit a Gaussian process regression model toa dataset. A Gaussian process (GP) is a commonly used model in computersimulation. It assumes that the distribution of any set of points ismultivariate normal. A major benefit of GP models is that they provideuncertainty estimates along with their predictions.

You can install like any other package through CRAN.

install.packages('GauPro')The most up-to-date version can be downloaded from my Githubaccount.

# install.packages("devtools")devtools::install_github("CollinErickson/GauPro")This simple shows how to fit the Gaussian process regression model todata. The functiongpkm creates a Gaussian process kernelmodel fit to the given data.

library(GauPro)#> Loading required package: mixopt#> Loading required package: dplyr#>#> Attaching package: 'dplyr'#> The following objects are masked from 'package:stats':#>#> filter, lag#> The following objects are masked from 'package:base':#>#> intersect, setdiff, setequal, union#> Loading required package: ggplot2#> Loading required package: splitfngr#> Loading required package: numDeriv#> Loading required package: rmarkdown#> Loading required package: tidyrn<-12x<-seq(0,1,length.out = n)y<-sin(6*x^.8)+rnorm(n,0,1e-1)gp<-gpkm(x, y)#> * Argument 'kernel' is missing. It has been set to 'matern52'. See documentation for more details.Plotting the model helps us understand how accurate the model is andhow much uncertainty it has in its predictions. The green and red linesare the 95% intervals for the mean and for samples, respectively.

gp$plot1D()

diamonds datasetThe model fit usinggpkm can also be used withdata/formula input and can properly handle factor data.

In this example, thediamonds data set is fit byspecifying the formula and passing a data frame with the appropriatecolumns.

library(ggplot2)diamonds_subset<- diamonds[sample(1:nrow(diamonds),60), ]dm<-gpkm(price~ carat+ cut+ color+ clarity+ depth, diamonds_subset)#> * Argument 'kernel' is missing. It has been set to 'matern52'. See documentation for more details.Callingsummary on the model gives details about themodel, including diagnostics about the model fit and the relativeimportance of the features.

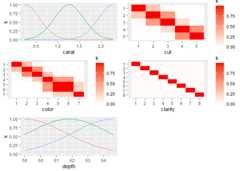

summary(dm)#> Formula:#> price ~ carat + cut + color + clarity + depth#>#> Residuals:#> Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.#> -6589.09 -217.68 37.85 -165.28 181.42 1619.37#>#> Feature importance:#> carat cut color clarity depth#> 1.5497 0.2130 0.3275 0.3358 0.0003#>#> AIC: 1008.96#>#> Pseudo leave-one-out R-squared : 0.901367#> Pseudo leave-one-out R-squared (adj.): 0.8427204#>#> Leave-one-out coverage on 60 samples (small p-value implies bad fit):#> 68%: 0.7 p-value: 0.7839#> 95%: 0.95 p-value: 1We can also plot the model to get a visual idea of how each inputaffects the output.

plot(dm)

In this case, the kernel was chosen automatically by looking at whichdimensions were continuous and which were discrete, and then using aMatern 5/2 on the continuous dimensions (1,5), and separate orderedfactor kernels on the other dimensions since those columns in the dataframe are all ordinal factors. We can construct our own kernel usingproducts and sums of any kernels, making sure that the continuouskernels ignore the factor dimensions.

Suppose we want to construct a kernel for this example that uses thepower exponential kernel for the two continuous dimensions, orderedkernels oncut andcolor, and a Gower kernelonclarity. First we construct the power exponential kernelthat ignores the 3 factor dimensions. Then we construct

cts_kernel<-k_IgnoreIndsKernel(k=k_PowerExp(D=2),ignoreinds =c(2,3,4))factor_kernel2<-k_OrderedFactorKernel(D=5,xindex=2,nlevels=nlevels(diamonds_subset[[2]]))factor_kernel3<-k_OrderedFactorKernel(D=5,xindex=3,nlevels=nlevels(diamonds_subset[[3]]))factor_kernel4<-k_GowerFactorKernel(D=5,xindex=4,nlevels=nlevels(diamonds_subset[[4]]))# Multiply themdiamond_kernel<- cts_kernel* factor_kernel2* factor_kernel3* factor_kernel4Now we can pass this kernel intogpkm and it will useit.

dm<-gpkm(price~ carat+ cut+ color+ clarity+ depth, diamonds_subset,kernel=diamond_kernel)dm$plotkernel()

A key modeling decision for Gaussian process models is the choice ofkernel. The kernel determines the covariance and the behavior of themodel. The default kernel is the Matern 5/2 kernel(Matern52), and is a good choice for most cases. TheGaussian, or squared exponential, kernel (Gaussian) is acommon choice but often leads to a bad fit since it assumes the processthe data comes from is infinitely differentiable. Other common choicesthat are available include theExponential, Matern 3/2(Matern32), Power Exponential (PowerExp),Cubic, Rational Quadratic (RatQuad), andTriangle (Triangle).

These kernels only work on numeric data. For factor data, the kernelwill default to a Latent Factor Kernel (LatentFactorKernel)for character and unordered factors, or an Ordered Factor Kernel(OrderedFactorKernel) for ordered factors. As long as theinput is given in as a data frame and the columns have the proper types,then the default kernel will properly handle it by applying the numerickernel to the numeric inputs and the factor kernel to the factor andcharacter inputs.

Kernels are stored as R6 objects. They can all be created using theR6 object generator (e.g.,Matern52$new()), or using thek_<kernel name> shortcut function (e.g.,k_Matern52()). The latter is easier to use (andrecommended) since R will show the function arguments andautocomplete.

The following table shows details on all the kernels available.

| Kernel | Function | Continuous/ discrete | Equation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian | k_Gaussian | cts | Often causes issues since it assumes infinite differentiability.Experts don’t recommend using it. | |

| Matern 3/2 | k_Matern32 | cts | Assumes one time differentiability. This is often too low of anassumption. | |

| Matern 5/2 | k_Matern52 | cts | Assumes two time differentiability. Generally the best. | |

| Exponential | k_Exponential | cts | Equivalent to Matern 1/2. Assumes no differentiability. | |

| Triangle | k_Triangle | cts | ||

| Power exponential | k_PowerExp | cts | ||

| Periodic | k_Periodic | cts | \(k(x, y) = \sigma^2 *\exp(-\sum(\alpha_i*sin(p * (x_i-y_i))^2))\) | The only kernel that takes advantage of periodic data. But there isoften incoherence far apart, so you will likely want to multiply by oneof the standard kernels. |

| Cubic | k_Cubic | cts | ||

| Rational quadratic | k_RatQuad | cts | ||

| Latent factor kernel | k_LatentFactorKernel | factor | This embeds each discrete value into a low dimensional space andcalculates the distances in that space. This works well when there aremany discrete values. | |

| Ordered factor kernel | k_OrderedFactorKernel | factor | This maintains the order of the discrete values. E.g., if there are3 levels, it will ensure that 1 and 2 have a higher correlation than 1and 3. This is similar to embedding into a latent space with 1 dimensionand requiring the values to be kept in numerical order. | |

| Factor kernel | k_FactorKernel | factor | This fits a parameter for every pair of possible values. E.g., ifthere are 4 discrete values, it will fit 6 (4 choose 2) values. Thisdoesn’t scale well. When there are many discrete values, use any of theother factor kernels. | |

| Gower factor kernel | k_GowerFactorKernel | factor | \(k(x,y) = \begin{cases} 1, & \text{if} x=y \\ p, & \text{if } x \neq y \end{cases}\) | This is a very simple factor kernel. For the relevant dimension, thecorrelation will either be 1 if the value are the same, or |

| Ignore indices | k_IgnoreIndsKernel | N/A | Use this to create a kernel that ignores certain dimensions. Usefulwhen you want to fit different kernel types to different dimensions orwhen there is a mix of continuous and discrete dimensions. |

Factor kernels: note that these all only work on a single dimension.If there are multiple factor dimensions in your input, then they eachwill be given a different factor kernel.

Kernels can be combined by multiplying or adding them directly.

The following example uses the product of a periodic and a Matern 5/2kernel to fit periodic data.

x<-1:20y<-sin(x)+ .1*x^1.3combo_kernel<-k_Periodic(D=1)*k_Matern52(D=1)gp<-gpkm(x, y,kernel=combo_kernel,nug.min=1e-6)#> * nug is at minimum value after optimizing. Check the fit to see it this caused a bad fit. Consider changing nug.min. This is probably fine for noiseless data.gp$plot()

For an example of a more complex kernel being constructed, see thediamonds section above.

(This section used to be the main vignette on CRAN for thispackage.)

This R package provides R code for fitting Gaussian process models todata. The code is created using theR6 class structure,which is why$ is used to access object methods.

A Gaussian process fits a model to a dataset, which gives a functionthat gives a prediction for the mean at any point along with a varianceof this prediction.

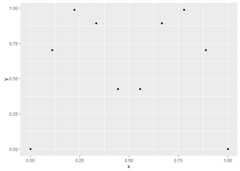

Suppose we have the data below

x<-seq(0,1,l=10)y<-abs(sin(2*pi*x))^.8ggplot(aes(x,y),data=cbind(x,y))+geom_point()

A linear model (LM) will fit a straight line through the data andclearly does not describe the underlying function producing thedata.

ggplot(aes(x,y),data=cbind(x,y))+geom_point()+stat_smooth(method='lm')#> `geom_smooth()` using formula = 'y ~ x'

A Gaussian process is a type of model that assumes that thedistribution of points follows a multivariate distribution.

In GauPro, we can fit a GP model with Gaussian correlation functionusing the functiongpkm.

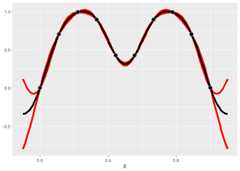

library(GauPro)gp<-gpkm(x, y,kernel=k_Gaussian(D=1),parallel=FALSE)Now we can plot the predictions given by the model. Shown below, thismodel looks much better than a linear model.

gp$plot1D()

A very useful property of GP’s is that they give a predicted error.The red lines give an approximate 95% confidence interval for the valueat each point (measure value, not the mean). The width of the predictioninterval is largest between points and goes to zero near data points,which is what we would hope for.

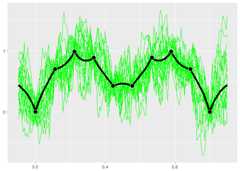

GP models give distributions for the predictions. Realizations fromthese distributions give an idea of what the true function may looklike. Calling$cool1Dplot() on the 1-D gp object shows 20realizations. The realizations are most different away from the designpoints.

if (requireNamespace("MASS",quietly =TRUE)) { gp$cool1Dplot()}

The kernel, or covariance function, has a large effect on theGaussian process being estimated. Many different kernels are availablein thegpkm() function which creates the GP object.

The example below shows what the Matern 5/2 kernel gives.

kern<-k_Matern52(D=1)gpk<-gpkm(matrix(x,ncol=1), y,kernel=kern,parallel=FALSE)if (requireNamespace("MASS",quietly =TRUE)) {plot(gpk)}

The exponential kernel is shown below. You can see that it has a hugeeffect on the model fit. The exponential kernel assumes the correlationbetween points dies off very quickly, so there is much more uncertaintyand variation in the predictions and sample paths.

kern.exp<-k_Exponential(D=1)gpk.exp<-gpkm(matrix(x,ncol=1), y,kernel=kern.exp,parallel=FALSE)if (requireNamespace("MASS",quietly =TRUE)) {plot(gpk.exp)}

Along with the kernel the trend can also be set. The trend determineswhat the mean of a point is without any information from the otherpoints. I call it a trend instead of mean because I refer to theposterior mean as the mean, whereas the trend is the mean of the normaldistribution. Currently the three options are to have a mean 0, aconstant mean (default and recommended), or a linear model.

With the exponential kernel above we see some regression to the mean.Between points the prediction reverts towards the mean of 0.2986876.Also far away from any data the prediction will near this value.

Below when we use a mean of 0 we do not see this same reversion.

kern.exp<-k_Exponential(D=1)trend.0<- trend_0$new()gpk.exp<-gpkm(matrix(x,ncol=1), y,kernel=kern.exp,trend=trend.0,parallel=FALSE)if (requireNamespace("MASS",quietly =TRUE)) {plot(gpk.exp)}