A power user’s guide to OS X Server, Yosemite edition

Apple’s server hardware is all gone, but its software is still going strong.

OS X Server is in maintenance mode. That much was clearwhen Mavericks Server came out a year ago with just a handful of welcome-but-minor tweaks and improvements. The software hasn’t grown stagnant, really—certainly not to the extent of something like Apple Remote Desktop, which only gets updated when it’s time to support a new OS X version. But now OS X Server is changing very little from version to version, and sincethe untimely death of the Mac Mini Server, Apple isn’t even selling any kind of server-oriented hardware.

Still, the Yosemite version of OS X Server changes enough to be worth revisiting. As with our pieces onMavericks andMountain Lion, this article should be thought of as less of a review and more of a guided tour through everything you can do with OS X Server. We’ll pay the most attention to the new stuff, but we’ll also detail each and every one of OS X Server’s services, explaining what it does, how to use it, and where to find more information about it. In cases where nothing has changed, we have re-used portions of last year’s review with updated screenshots and links.

Installation, setup, and getting started

When configuring a new OS X Server, the install process is the same as it was in Mavericks: take any Mac running OS X 10.10 and download and install the Server software package (hereafter Server.app) from the Mac App Store. Unlike Yosemite itself, Server.app 4.0 is still a $19.99 download both for new customers and for people upgrading from Mountain Lion or Lion Server, though download codes are being offered free of (additional) charge to members of Apple’s $99-a-year OS X and iOS developer programs. The older Server.app versions won’t run in Yosemite, and Server.app 4.0 won’t run under older OS X versions. The upgrade process is an all-or-nothing proposition.

Apple has removed most of the more intimidating configuration screens from the Server installation process. Where Mountain Lion Server and older versions would ask for hostname and IP address configuration (among other things), the new Server.app gets right to the point. Agree to the EULA, input an administrator’s username and password, and wait for the first-time setup process to complete. Configuring those more advanced settings can still be done after the fact in Server.app, but for home users, the more intimidating barriers to installation have been removed.

One new addition to Yosemite Server’s setup is the ability to “use Apple’s services to determine Internet reachability.” This is a handy feature that takes some of the guesswork out of configuring services that you need to access from outside your local network, which can be especially tricky if you’ve never played with port forwarding before. The feature does require some information about your server to be sent to Apple. The company has buried information about this service in its EULA, but we’ve pasted the relevant section below. The short version is that Apple doesn’t store most of the information you send it, but it can retain your external IP address for up to 24 hours. Opting in isn’t mandatory, so if you’re not comfortable with this feature you don’t need to use it.

Unless you opt out in the Reachability pane of the Apple Software or uncheck the box at the bottom of this License page, the Apple Software will perform network diagnostic tests to assist you in setting up, configuring and monitoring your Apple Server to determine if it is functioning properly and how it is accessible over the Internet. As part of performing these tests, you agree that Apple will query your Apple Server and that your external IP address, configured mail domain, and the port numbers of running server services on your Apple Server will be accessed and displayed within the Apple Software. This information will be sent to Apple to provide you with network diagnostic test results and will not be retained, except that Apple will retain your external IP address for 24 hours solely for quality assurance and capacity planning purposes for the Apple Software.

Beginning in Mavericks, Apple started offering simplified, user-friendly Server Tutorials to help newcomers configure the services they want to use. Older versions of Server.app had a persistent “Next Steps” area across the bottom of the screen that would assist newbies through some of the server basics, but the Server Tutorials are more friendly and more comprehensive all around. The stuff that will be of the most interest to home users—Time Machine, VPN, File Sharing, caching of iOS and OS X app and update downloads—is well-represented here.

Each tutorial starts with an objective stated in plain language: “share files” or “provide centralized backup” or “host a website.” Clicking on each section opens up a tutorial that explains services like File Sharing and Time Machine at a high level before providing step-by-step instructions with screenshots and some resources for further reading. The “Advanced Topics” section of Apple’s online OS X Server help is generally the first stop.

Apple’s online help and the old-style Server Help files are all still there in the Yosemite version of OS X Server, but the new Server Tutorials fill a pretty obvious user education gap from older versions of the software. Along with the simplification of the setup process, they make it easier for a Mac enthusiast to make the jump from being a regular old OS X user to an amateur server administrator. Learning OS X Server in the olden days was a study in digging into Help files, Googling, and just poking around at stuff until it seemed like it was working. The tutorials provide new users a clearer path from Point A to Point B, and the Internet Reachability feature helps to confirm that you’ve set things up properly.

Server.app basics

If you want to do basically anything with OS X Server, you’re going to do it with Server.app. This all-in-one server administration tool has completely replaced the more advanced but less user-friendly Server Admin Tools from Lion and older versions of OS X, but it supports most of the same features. Like the rest of Yosemite, Server.app has gotten a new facelift with less texture, lighter fonts, and thinner lines, but functionally the app remains much the same as it was in Mavericks.

Aside from the redesign, Yosemite’s Server.app brings a couple features to the table, both of which are designed to make your server easier to configure: the ability to see at a glance which of your services are reachable from the Internet and how to reach them. Many of OS X Server’s features are going to work just fine on an internal network—the Caching service, Time Machine, and File Sharing don’t need external connectivity to work, and you may even prefer that they be sequestered from the wider Internet. Others, like Mail, VPN, and Websites were designed to be used whether you’re at home or not, and the Internet Reachability feature is an easy way to confirm that you’ll be able to reach these services from off-network.

A new feature in Yosemite Server is the “Access” tab, which is used for a couple different things. For one, it’s an easy way to see which ports you need to open in your router’s firewall to provide external access to every service your server offers. It can also be used to restrict access to certain services—you can restrict them to certain users just as you could in older OS X Server versions, but in Yosemite you can define network-based access rules too. Services can be restricted so that they only work on your server’s local network or on specific outside networks. These controls are useful if you’d like to provide services for, say, family members or coworkers on specific external networks, but not to the Internet at large.

All the stuff you could do in the last version of Server.app is still here too. Here’s the quick rundown:

- Manage local and Open Directory users and groups

- Enable, disable, and configure services, all of which we’ll be discussing individually

- Add SSL certificates

- Set remote management preferences

- Enable push notifications

- Check your server’s status and log messages

- View hardware usage stats including CPU, RAM, and network traffic, and a few other stats for individual services

You can launch Server.app directly on the server itself, or you can install it on any OS X client computer and connect to properly configured Yosemite servers using their host names or IP addresses—just click Connect to Server from the Manage menu. Server.app in Mavericks is able to manage both Yosemite servers and older Mavericks servers, butaccording to this Apple support document it can no longer manage Mountain Lion servers. If you manage multiple servers and don’t want to upgrade all of them at once, you’ll be able to use the same tool to control all of them as long as they’re running either Yosemite or Mavericks.

Looking at the left of the window, start at the top and work your way down. Items in the “Server” section are all about server monitoring and general administration. This is where you can view uptime and log information, usage statistics, log files from your various services, and any alerts that the server may have generated. Yosemite retains all of the alert types used in Mavericks—you can receive notifications about many services and your disk and firewall status—and adds alerts for Xcode Server and Xsan.

The first entry will have your server’s name and a small picture of the kind of Mac you’re using. From this menu, you can view and change the server’s IP address and hostname information, import and manage security certificates, and configure the server’s remote administration options. Your server can be managed remotely using SSH, screen sharing, or other client Macs running Server.app.

This menu is also used to configure push notifications for your services. Push notifications are used with the Mail, Contacts, Calendar, and Profile Manager services to alert your users when new messages or calendar invites or other data comes in. Apple’ssupport documentation recommends using push notifications with these services as a more efficient alternative to polling the server for data at a set interval. Additionally, push notifications are used to alert server administrators when new Alerts are generated—any Mac that has connected to your server using Server.app will receive these Alerts in its Notification Center.

Push notifications can be sent from your server to any OS X or iOS client that it manages. You first need to get a Push Notification Service certificate from Apple using an organizational Apple ID as opposed to the personal Apple ID that you might use in the Mac App Store or with an Apple Developer account. The certificate, which is used to encrypt the communication between your server and your clients, is free, but it must be renewed yearly.

We’ll talk more about Server.app’s “Accounts” heading later in the Open Directory section, since it’s mostly useful for administrators of small to medium-size businesses using their Macs to manage user credentials and permissions (for home users, using the user account management included in the System Preferences will likely be sufficient). The panes for Server’s various services are where you’ll spend the vast majority of your time in OS X Server, and we’ll be going through each service one by one to explain their particular uses and features.

Each service has its own particular configuration options, but a few items are universal across all Service panes. One is the giant on/off switch at the top-right that is used to enable and disable the service (disabling the service doesn’t delete its settings, it simply turns the service off). The other is the Access section, which gives you more granular status messages about what the service is doing at a particular point in time. Most of the time this message will just tell you whether the service is on or off, but OS X Server tries to be as user-friendly and unambiguous as possible. Each service also includes a link to an OS X Server help file with more information for each service. This information will mostly be redundant or unnecessary for advanced users, but Apple is working to make Server easier to learn for people new to the software.

Finally, there’s a separate section in Server.app for “Advanced” services, including DHCP, DNS, FTP, NetInstall, Open Directory, Software Update, and Xsan. These services are all hidden by default in the View menu (to keep newbies from stumbling onto them, one assumes), but clicking any of them will cause all of them to show up in Server.app as they normally would in Mountain Lion. We’ll be going through all of them to talk about what they do, but unlike some of the non-advanced services, these have seen very little change in Yosemite (or in Mountain Lion or Mavericks, for that matter).

OS X Server and AirPort

There’s one thing we should talk about that has been a feature of OS X Server for a while, but we haven’t covered before because we haven’t had one of Apple’s AirPort routers sitting around.

Normally, if you want to make one or more of OS X Server’s services available outside of your home network, it involves configuring port forwarding and poking small holes in your router’s firewall. The interfaces for doing this can vary from router to router, and on some routers (usually older or lower-end models) it may not be an option at all. The Internet Reachability feature helps you confirm whether you’ve set things up correctly, but not with the setup itself.

If you’ve got an AirPort Express or Extreme, things get significantly easier. Enter your AirPort’s admin password and click the plus button to add any of the listed services to the “Public Services” list. Once added, Server.app will automatically configure your router properly. If you’ve got Open Directory configured you can even decide to configure your router to useRADIUS authentication, allowing users to connect to the network with their own usernames and passwords instead of a shared WPA2 passkey.

Is any of this strictly necessary? No. But it’s another example of how Apple tries to make its hardware and software work better together.

Open Directory

Open Directory is one of the core services of OS X Server, and since we’ll be talking about users, groups, and permissions a lot in the next few thousand words, we’ll talk about it first (even if it has been stuck below the “Advanced” services fold in Yosemite).

Open Directory is an LDAP-based directory system that allows you to create and manage user accounts and groups of user accounts. Like Microsoft’s Active Directory, it allows your users to log in to computers and services using one username and password. Administrators can use it to enforce preferences and security settings on Macs and iOS devices, which we’ll get into when we talk about the Profile Manager.

Open Directory creation and administration is handled completely within Server.app—open the service and switch it on to trigger the configuration wizard.

We’ll be creating a new Open Directory domain for our testbed, but note that you can also bind one Open Directory server to another to create a replica server, which will provide redundancy in the case of server failure. If any of your servers go down, your client computers should automatically fail over to one of the working replicas until the borked machine comes back up. If you have multiple Open Directory servers, you can use the Locales feature to assign different servers to different network subnets to help with load balancing. Your master and replica Open Directory servers will all need to be running the same version of OS X Server, though—you may run into error messages if you try to mix-and-match.

While setting up a new Open Directory, you’ll be asked to set up a directory administrator account that’s separate from the administrator account used to manage the server itself. We’ll stick with the default “diradmin” username for our purposes, but the account can be named anything you want. Once you’ve finished this step, you’re basically done with setup, unless you need to do more advanced network configuration. The Locales pane allows you to specify which of your client subnets will connect to which of your directory servers, for example. Once you’ve got this set up to your liking, you can turn to the Users and Groups sections to begin building your directory.

Users and Groups

Users and user groups are now managed exclusively by Server.app. Three different kinds of users can live on your Open Directory server: local user accounts that can only log in to the server itself, network user accounts that can log in to computers bound to your directory and make use of your server’s services, and network service accounts that can only be used to access services. You can view, create, and edit all these types of users in the Users pane.

When creating network users, you must give them a full name, a short name, and a password, and you can also enter an e-mail address for them. The Contacts service pulls from Open Directory to autofill names and e-mail addresses, so be sure to input the information just as you’d like to see it. The Home Folder drop-down menu is where you choose whether to make this a standard network account or a service account.

If you set up a file share to store user Home folders in the File Sharing service, you can choose whether to let your network users have their profiles stored on the hard drives of Macs they log in to or whether the profile is saved to the server. The second option is Apple’s version of Microsoft’s Roaming Profiles. Logging in and working with files can be a bit slower due to network latency, but all of the users’ files and settings are automatically available no matter what computer they’re using. These can follow a user around from computer to computer.

Using the Disk Quota field, you can limit the amount of server space a user’s profile is allowed to consume. It’s worth noting that this quota amount doesn’t apply to all services—Mail accounts have their own quotas, as do Time Machine backups (this is a feature we’ll examine more later on).

Once created, you can manage users’ access to individual services on your server—allowing them to use Mail, for example, without being able to access Time Machine or the VPN. Within the Users pane, you can also set password policies (including things like minimum length and expiration dates), and the Edit Mail Options field allows you to set up mail forwarding for individual accounts if you won’t be giving them access to their own e-mail account on your server.

If you have a large number of users, splitting them up into groups and managing their settings that way may be more convenient. While you can’t set disk quotas and home directories to entire groups of users, you can grant and block groups’ access to services. You can also give each of your groups a file share, a Wiki page, and a group mailing list, and you can automatically make group members buddies in the Messages application if you have the service turned on.

Comparison with Active Directory

Open Directory is without a doubt simpler to configure than a full-blown Active Directory implementation. Configuring users and groups in Server.app is also much simpler than it was in the old Workgroup Manager—it’s pretty much the same as it’s been since Server.app was introduced. For a home or small Mac-centric business, the barrier to entry is unquestionably lower, and you’ll be able to get a directory up and running without much time investment.

That simplicity comes at the cost of features, however. Most notably, Open Directory lacks any of the software installation features of Active Directory, though the Profile Manager can be used to distribute internal apps and App Store apps in some cases. Administrators can rely on Apple Remote Desktop or a third-party product like theCasper Suite for the installation and patching of third-party applications. Operating system and first-party software updates can be managed through the legacy Software Update service or by the Caching service if you’re comfortable with a more hands-off approach.

Another missing feature (one that has been missing since Snow Leopard) is the ability to bind Windows computers to an Open Directory server. For mixed networks of Windows and OS X computers, Apple now tells server admins to bind Macs to both an Active Directory serverand an Open Directory server, a configuration it calls a “magic triangle”—the Active Directory server handles authentication and settings for the Windows computers and authentication for the Macs, while the Open Directory server controls settings for Macs. It’s a pretty big feature to lose, though in practice most businesses aren’t going to notice. Active Directory is more or less ubiquitous in the enterprise, so it’s usually enough for OS X Server to be able to integrate with those existing directories rather than trying to supplant them.

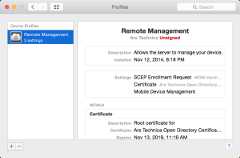

Profile Manager

After Open Directory, Profile Manager is probably the most valuable service included in OS X Server. With it, you can create and disseminate configuration profiles to your Macs and iOS devices, automatically configuring everything from e-mail accounts to passcode requirements to Dock icons. Once clients have installed one of your configuration profiles, you can also push out updated settings automatically if you have a Push Notifications certificate enabled on your server.

Profiles are created in the form of .mobileconfig files, the same sort of files that are created by the iPhone Configuration Utility and theApple Configurator, but they can also be used to manage Macs. Once you’ve enabled the Profile Manager, enable Device Management and enter the settings it wants—an organization name and e-mail address and an SSL certificate—and you’ll be ready to start managing devices.

Yosemite makes few changes to the way Profile Manager looks or works—it focuses mostly on adding settings to manage some of the new features in iOS 8 and OS X Yosemite. Administrators can now restrict use of Handoff, whether Internet suggestions come up in Spotlight, cellular data use, and a handful of othersspelled out in the release notes. The full list of options is too long to go through here, but generally speaking if you can configure a setting locally on the device, Profile Manager gives you the ability to configure those settings. On top of that, it adds a bunch of other features used to limit the ways devices can be used (and abused, as the case may be).

The default profile is called “Settings for Everyone” and can be configured or replaced by using the Web-based Profile Manager portal. For services that you’ve configured—Mail, VPN, Calendar, and a few others—keeping the “Include configuration for services” box checked when you edit the Settings for Everyone profile is an easy way to make sure everyone connected to your network can at least have access to those services. If you need more granular options, click the Open Profile Manager link in Server.app, which is also accessible by typing [server.address]/profilemanager into your browser of choice.

Once in Profile Manager, you can view all of the users and groups we created in Open Directory earlier. We can also see fields for devices and device groups, but they aren’t populated yet. To make things show up there, we’ll need to navigate to the Profile Manager login page at[server.address]/myprofiles from each of the devices you want to manage. iPhones, iPads, iPod Touches, and Macs running OS X 10.7, 10.8, 10.9, or 10.10 are all enrolled and managed pretty much the same way. Older OS X versions are not supported by Profile Manager, and if certain features require a minimum version of OS X, they’ll generally say so.

Once you’ve signed in using a network user account, you’ll be presented with a big blue button that will let you enroll your device. Once enrolled, it will show up in your administrator’s Profile Manager, where you can view, edit, and push out new settings as desired. If you’re working with a self-signed SSL certificate, you may also need to install the Trust Profile for your organization from the Profiles tab before your devices will be able to install your profiles. One setting within the profile controls whether that profile can be removed from devices by users after the fact. If you don’t want people removing your profile and potentially compromising your security, make sure you configure that particular option.

After devices are enrolled, administrators can view them, lock or wipe them, and arrange them into groups for easier administration. iOS devices can even have their passcodes andActivation Locks cleared in case of emergency, though obviously you shouldn’t use this feature lightly. Detailed hardware information, including MAC addresses, UDIDs, IMEI numbers, and specific model and software information, is stored in the server—for iOS devices you can even see the battery life level as of the last check-in. It’s a powerful tool for administrators looking to track their hardware. Users can also lock and wipe devices on their own without intervention from an administrator.

Mavericks introduced some additional app distribution options to the Profile Manager. Most notably, you can distribute apps and media you’ve purchased as part of Apple’sVolume Purchase Program for businesses and educational institutions, a natural fit given Apple’s push into the textbook market. Additionally, the VPP can be used to deliver apps built specifically for your business that aren’t publicly available in the App Store, and the Profile Manager can distribute in-house apps developed through theiOS Developer Enterprise Program.

Tech Republic hasa nice overview of what is required to get into the VPP program, which involves confirming that you are who you say you are and that you’re authorized to purchase apps on behalf of your institution. Once you do, you’ll need to download a VPP token and plug it into Server.app to manage your purchases. Using OS X Server along with the VPP site, you should be able to automate installation, uninstallation, and license tracking for the apps and books you buy (similar functionality is also being introduced in other mobile device management services likeMaaS360).

Almost every setting available in the iOS Settings app or OS X’s System Preferences window can be controlled using the .mobileconfig files generated by Profile Manager. Click Edit and you’ll see all of the settings you can configure. Some, like Mail, VPN, security certificates, and wireless network settings can be configured for both OS X and iOS, while others are restricted specifically to iOS (device restrictions like the use of iCloud backups or in-app purchases) or OS X (Dock icons, Gatekeeper settings, roaming profiles, printer settings, and others). You can also upload custom .plist files to apply to your OS X computers to configure third-party apps not accounted for in the Profile Manager, and you can deploy volume-licensed iOS apps.

Profile Manager is a powerful tool for directory administrators, and it’s also usable if you have a large number of OS X and iOS devices at home (or if your children have their own iOS devices and you’d like to be able to set universal restrictions on them). You’ll just have to decide if managing the devices centrally is more of a hassle than just configuring each one manually.

RIP Workgroup Manager, last of the Server Admin Tools

Back in OS X 10.6 and 10.7 when the full Server Admin Tools package was still a thing, users, groups, and computers were all managed through something called the Workgroup Manager. It was about as user-friendly as its name implies.

After the Server Admin tools package was discontinued in version 10.8, Workgroup Manager lived on as a small separate download that could be used to do directory management and manage settings for older Macs, those too old to use the configuration profiles generated by Profile Manager. Workgroup manager held on through 10.9, but Apple’s support documentation says thatWorkgroup Manager is no longer compatible with Yosemite. It’s the end of the line.

Obviously in a best-case scenario, you wouldn’t still have Macs running Tiger, Leopard, and Snow Leopard on your network any more. Apple has long sincestopped providing security and feature updates for those aging versions of OS X, and at this point everything on your network should really be new enough to run Mountain Lion, Mavericks, and Yosemite (the three share identical system requirements).

If you do need to manage older Macs, you could still keep a Mavericks server sitting around, since it can still be managed with Yosemite’s version of Server.app, but this should be considered a stopgap solution. Profile Manager and Server.app are now the tools you use to manage devices and user accounts on your network—start using them.

File Sharing

As ever, the File Sharing service in Yosemite is an extension of the file-sharing features in the client version of OS X, adding WebDAV support and more robust permissions management to the existing Apple File-sharing Protocol (AFP) and Server Message Block (SMB) protocols supported by the client version of the operating system. You can also enable encryption for your SMB share points here, and you can view the IP addresses, protocols, and usernames of all users connected to any of your shares.

After enabling the service, the system will create a number of default share points, all of which can be edited or deleted as needed. Click the plus button to add a new volume or folder as an additional share point, and then click the Settings button and “Edit share point” to adjust the permissions on the share. You can grant users read-only access, read and write access, or no access; allow or disallow guest access for a particular share; and choose to make certain shares available for the roaming user profiles that we touched upon earlier.

SMB 3.0: Optional encryption and performance improvements

OS X continues to lag a bit behind Windows when it comes to SMB support, but Yosemite comes pretty close to fixing that. It introduces support for SMB 3.0, which, in addition to increasing transfer speeds, introduces an option for end-to-end encryption. We already saw some nice performance improvements when Apple introduced SMB 2 support in Mavericks, which just about closed the longstanding performance gap between OS X’s SMB implementation and its implementation of Apple’s homegrown AFP protocol. In Mavericks,SMB became OS X’s file sharing protocol of choice, so it’s being improved while AFP stays as it is. Apple even removed a few AFP-exclusive features in Mavericks, including the ability to send greetings or messages to users connected to AFP shares.

SMB 3 shares must be encrypted individually, since there’s no universal setting for it. When encryption is enabled, Server.app automatically disables the AFP protocol for that share, since AFP doesn’t support encryption (and probably never will). It also means that clients running older operating systems with older SMB versions won’t be able to connect to your server—your clients will need to be running either Yosemite or Windows 8 or newer to connect to your server.

Now for some speed testing. For these tests, we’re comparing SMB performance in Mavericks and Yosemite by transferring files between computers connected to an Airport Extreme router with gigabit Ethernet cable. We’ve performed the same tests with encryption enabled and disabled to measure the impact that encryption has on file transfer performance. The “Large file” test copies one 4.6GB .dmg file from our server to the client. The “Small file” test copies 2.3GB of data spread across 978 files.

Looking at these charts, we can make three broad observations about file copy performance in Yosemite. First, SMB 3 is faster than SMB 2, but only by around 10 percent or so—it’s improved enough that you might notice for large transfers in the idealized test network we’ve set up, but it’s close. Second, for raw speed, AFP still edges out SMB 3 by a tiny margin, even though the protocol hasn’t been improved since Mavericks. Third, enabling encryption on an SMB 3 share will slow you down by 10 or 15 percent, depending on what kind of files you’re copying. This is enough to absorb the speed increases SMB 3 brings, but if you’re transferring files over the Internet it’s a small price to pay for the improved security.

WebDAV

WebDAV sharing works the same way it did in Mavericks, and it’s still persnickety about who can use it and how WebDAV shares are accessed. Most notably, the service will only allow Open Directory users, not users local to your server, to access WebDAV shares. You’ll also need the precise URL for every share point you’d like to access; the format ishttp(s):///webdav/. Once we were doing all of these things properly, we were able to connect to WebDAV shares from both OS X and Pages and copy some documents back and forth.

FTP and SFTP

FTP sharing isn’t part of the core File Sharing service, though it is closely related. The FTP service in OS X Server can be used to share one of your AFP or SMB shares from the File Sharing service or one of the sites you’ve configured with the Websites service, or you can elect to create a custom standalone share. However, you can only have one FTP share point configured at a time, making it a poor choice if you’re serving several sites you’d like to access via FTP.

Remember, there’s no security inherent to the FTP protocol, and by default any data you send or receive from an FTP share point will be unencrypted. If you’d like to enable encrypted SFTP transfers instead, enable remote login using SSH from your server’s settings as shown above. You can also do this from within System Preferences on the server. Go to Sharing and enable Remote Login, which will enable SFTP along with the SSH remote login service. Enabling SSH enables SFTP—there’s no way to have one without the other, and there’s no way to serve standard FTP with SSH enabled.

Time Machine

If you don’t have a NAS device that supports Time Machine backups, the service in OS X Server is a useful way for home users to back up their Macs without having to plug an external drive in. Turn on the service, select the folder you’d like to store your backups in, and then select your server from the list of available backup disks on each client you’d like to back up.

In Mavericks, Apple introduced a small but significant feature that makes Time Machine much more useful and partially addresses our older complaints about the service’s inflexibility. When creating a backup destination folder, you can set a limit to the amount of space backups can consume. Pre-Mavericks versions of Time Machine would just keep filling up your drive until there wasn’t any free space left, at which point (and not before) it would begin to delete older files.

If you’re just using the Time Machine service by itself, that’s the sum total you can do to customize how Time Machine works. Server.app provides no interface for setting different quotas for different devices or different users or for setting up Time Machine on client Macs remotely. But something we’ve overlooked in the past is how Profile Manager can be used to address some of our gripes with Time Machine as a standalone service.

In Profile Manager, you can configure Time Machine payloads for individual Macs or groups of Macs that point the computers at your server, give them device-specific disk quotas, and even control what does and doesn’t get backed up (you can back up user data folders without using space for system files or applications, for instance). Rather than using the Time Machine service itself, you just need to make sure there’s an AFP share available that your clients can write to, and OS X takes care of the rest (AFP is still required for Time Machine, though Apple is moving to SMB as its default file transfer protocol).

Using Profile Manager to do this stuff has some downsides. It requires the setup and maintenance of a separate and much more complicated service that’s not as easy to configure or use. Since you’re telling your client Mac to backup to a file share, you’re bypassing the “real” Time Machine service and giving up some of the monitoring features it gives you. We’d say that Profile Manager is probably the way to go if you’re backing up a small office full of Macs, but that the Time Machine service is better for people backing up a few Macs at home.

If you still need more than what Time Machine can get you or if disk space is a concern, a paid alternative likeCrashPlan is still worth looking into.

Xcode

The developer-centric Xcode service, first introduced in Mavericks Server, allows you to set up a local Xcode repository so that several people (or one person on several computers, if that’s your thing) can easily access and change a single Xcode project at the same time. If you’re an iOS developer, you’ll need to sign in with a paid-up Apple developer account to use the service.

Setting the service up is relatively simple: you have to install Xcode on your server to build projects with, and you’ll need to create your own Git repository to store your code (support for external Git and SVN repositories appears to have been removed). Communication between the server and its clients can happen over HTTPS or SSH; unencrypted HTTP connections are no longer allowed. To test on iOS devices you’ve registered with your developer account, you also have to add at least one registered Apple Developer account to the “Developer Teams” section.

One of the core features of the Xcode service is the ability to create and run “bots,” processes that automate the continuous integration of your new code with your existing code. Bots can be scheduled to run at certain times (as often as hourly, as seldom as weekly) or can simply be set to run every time there’s a new code commit. By default, your bot will let people who have committed conflicting code know when they’ve committed conflicting code; you can also set bots up to notify committers about successful integrations and to e-mail third parties about both successful and unsuccessful integrations.

Bots need to be added from within Xcode itself on your development Mac—you’ll find the Create Bot setting under the Product menu. Like some other Xcode Server features, the ability to create them from the Web interface at[server.name]/xcode/bots appears to have been removed. From there, depending on the permissions you’ve configured in Server.app, your users can create and view bots, and logged in users can force a manual integration by hitting the “integrate” button.

Without being an OS X or iOS developer, it’s hard to really comment on whether the features that have been removed in the Yosemite version of OS X Server will be missed by anyone who was using the service in Mavericks. Start by digging through Apple’s documentation if you think you might like to use the Xcode service (as a place to start, there’s some enlightening information about the continuous integration featureshere). Like so many of OS X Server’s other services, it’s targeted at smaller shops made up of mostly Mac and iOS developers, and in that context it can be quite useful.

Caching

The Caching service was introduced late in Mountain Lion Server’s life, and it hasn’t changed a whole lot since then. Caching can be thought of as a modern-day replacement to the Software Update service. Where Software Update grabs OS X system updates and other Apple software (think iTunes and Safari updates, not updates handled through the Mac App Store) and stores it for local use, the Caching service grabs those updates in addition to content from the Mac and iOS App Stores, iBooks, iTunes U, and Internet Recovery files (the complete list of cacheable content ishere). It stores that data locally, and the next time a device on your network requests the same data, it downloads it from your server rather than Apple’s. This cuts down on the amount of traffic between your network and external servers.

Here’s how it works, with an illustration fromApple’s Help files to elucidate. Turn the Caching service on, and every time a Mac or iOS device on your local network requests any of the listed software from Apple’s servers, your local server will download and store a copy of that software. The next time a device on your local network tries to download that content, it will download from your local server instead of from Apple’s.

This both cuts down on your external bandwidth usage and can drastically speed up transfers—last year we downloaded the 5.29GB Mavericks installer to a MacBook Air via gigabit Ethernet in 12-and-a-half minutes when downloading the software from Apple’s servers. Deleting the installer and downloading it again after verifying that it had been cached shortened the download time to just over one minute. The more Macs and iOS devices you have hitting Apple’s servers for various software and app updates, the more bandwidth and time you’ll save.

The Caching service works with Macs running OS X 10.8.2 or later and iOS devices running iOS 7 or later. If you’re serving clients behind a single external IP address, that’s all you need to do—unlike the old Software Update service, the Caching service doesn’t require any additional configuration on your clients or that they be enrolled in Profile Manager or bound to your Open Directory. Every device on that network will trigger new downloads to the caching server and then download that data from your server instead of Apple’s. You can have as many VLANs set up as you want behind that external IP address, but they all need to be NAT’ed behind that external IP.

In Yosemite, Apple has added an option for admins who run non-NAT’ed networks—from experience, we can say that lots of educational institutions don’t need to do this, since they were often on the Internet before IP addresses began to become scarce. Click the Edit button next to the Permissions field, and you can specify ranges of IP addresses that you’d like the caching server to service. Once you’ve specified those ranges, adding a TXT record to your network’s DNS configuration allows your caching server to serve software to devices on those networks. You can choose what computers and what networks trigger caching of content, as well.

There are a few other server-side settings to look at as you configure the Caching service: you need to select which volume to cache the content on and how much of that volume’s free space the service can use. The service will begin deleting the least-used content when it reaches the space limit you specify (if you tell it to use “unlimited” space, it will start deleting things when the caching volume has less than 25GB of free space).

Finally, if you have more than one caching server on the same network, know that they will automatically consult one another to see which server (if any) has downloaded the data your client is requesting.

Software Update

The Software Update service is Apple’s equivalent of Microsoft’s Windows Server Update Services (WSUS). Your OS X server downloads updates directly from Apple’s software update servers. Then every client Mac you want to service must be pointed at your Software Update server instead of Apple’s, whether you do it individually by hand or en masse via the Profile Manager. Like the Caching service, this saves Internet bandwidth and increases the speed of large downloads, but it gives administrators a greater degree of control over what is being distributed (and works with Macs running operating systems much older than 10.8.2).

When set to Automatic, the service will automatically publish new updates to your Mac clients as they’re made available from Apple. Selecting Manual gives you the option to hold back updates for testing before pushing it out to all of your clients. Anyone who has ever installed a new OS X point update on the day it’s made available knows that you’re takinga certain amount of risk by doing so, and holding all butthe most critical security updates for at least a few days makes some sense if you’re trying to reduce support calls.

The Software Update service can update all of the same things that Apple’s servers can, including Mac firmware updates; updates for Safari, iTunes, and other Apple apps not handled through the Mac App Store (you can use the Caching service to handle updates for those); and system updates for OS X versions reaching all the way back to 10.4. A full copy of Apple’s update catalog is going to require several gigabytes of hard drive space. The ability to download and distribute iOS updates from your local server still isn’t included.

There are also a few other limitations here compared to something like WSUS. While you can hold updates back from your users, there’s no way to push them out. Once you’ve approved an update, your users can pull it down through the normal Software Update process, but you can’t mandate that the update be installed, and there’s no way to check update compliance throughout your organization. If your users choose to defer the updates, there’s really not much you can do about it. The best way to skirt this limitation is to use the Software Update service in concert with a management tool like Apple Remote Desktop, which can force update checks and install manually or on a schedule of your choosing.

Additionally, there’s no way to approve updates for certain groups or individuals while holding them back from other groups and individuals, functionality that WSUS has because of its tight Active Directory integration. Like many of OS X Server’s services, Software Update may be useful in a small business with Macs numbering in the low-to-mid double digits, but organizations with hundreds or thousands of Macs to manage may find that it doesn’t scale particularly well.

Areas of overlap, and advice for moving forward

If you’re running the Software Update service and the Caching service on the same server at the same time, there are a couple of things to keep in mind. First, since both services will cache system updates, you might end up storing the same update multiple times; OS X point updates are regularly over a gigabyte in size, so this could add up over time. However, since the Caching service only downloads things you and your users actually need, you won’t have to waste gigabytes of space on the ancient OS X updates that Software Update will download in Automatic mode.

Software Update gives you the ability to hold back certain updates for testing if you’d like, while Caching caches and serves everything without restriction. The same set-it-and-forget-it configuration that makes the Caching service so easy to start using also makes it difficult to live with if you need more granular or advanced controls.

At this point OS X Server has quite a few overlapping services and protocols, and it’s usually pretty clear which one is the “legacy” option and which one Apple intends to keep developing going forward. The Software Update service is clearly the legacy option here. More and more software updates for Apple products (including iLife, iWork, and all of its pro apps) are delivered through the Mac App Store rather than Software Update, and the Caching service is the only one that can store those updates locally. Software Update will keep working for the foreseeable future, but its users should be playing with the Caching service now if they aren’t already.

Mail, Calendar, Contacts, and Messages

Taken together, the Mail, Calendar, Contacts, and Messages services are OS X Server’s answer to Exchange, though none of them are nearly as complicated or feature-rich. Each service has seen relatively few changes since Mountain Lion, but we’ll check in on all of them just the same.

You can use the Mail service to provide POP and IMAP e-mail service for your domain and other domain names that you configure, and you can set the server to accept authentication from local users, Active Directory, and Open Directory users, depending on your server and network configuration. You can also add an SMTP mail relay if your Internet service provider puts you behind a firewall that prevents you from sending e-mail directly from your server, and you can set a universal e-mail quota for all accounts here as well (if a particular user needs a quota bump, you can override this setting in the Users panel). Mavericks Server could already be configured to serve e-mail for multiple domains, but Yosemite moves the feature front-and-center. Simple virus and junk mail filtering as well as support for third-party blacklist servers round out the service’s features.

Of the many things that Mail has lost since Lion (including the ability to easily set maximum attachment sizes and more flexible options for creating mailing lists), the webmail client is probably the one that people will notice the most.

That client, based on the open-sourceRoundcube client, could be politely described as “antiquated” and was in desperate need of an update (perhaps with the comparatively slick client that iCloud uses) but in Mavericks and Yosemite Apple has instead chosen to replace it with… nothing. You’ll have to rely on the built-in Mail clients in OS X and iOS (or your IMAP client of choice) by default, though if you’re really interested, you should be able to use the Websites service to manually install and configure a webmail front-end for your mail server. Otherwise, Mail is about as basic as IMAP mail services get. If your needs are such that they can’t be met by services hosted by the likes of Google and Microsoft, it’s likely that you’ll want something a little more powerful than this.

Calendar

The Calendar service gives each of your users their own calendar and Tasks list (which integrates with the Reminders apps in OS X and iOS) and will also let you create locations (like meeting rooms) and resources (like loaner laptops or projectors) that people can reserve. When creating locations and resources, you can either choose to let reservations be approved automatically or assign one of your users to be the delegate who approves and rejects them.

In Mavericks, Apple introduced an “Accept group” option to exclude certain groups from delegation; if you want managers to be able to reserve meeting rooms or equipment as they please but would like lower-level employees to have their requests vetted by the delegate, you just have to plug the user group or groups those managers belong to into that field. In Yosemite, Apple has added Maps integration that allows you to find and set specific addresses for locations.

Unlike Mail, the Calendar service’s Web client remains intact in Mavericks as long as you’ve also got the Websites service turned on, accessible from your browser athttp(s):///webcal. Using the Web client, you can create and view appointments and invitations, though you can’t see your Tasks lists from the Reminders apps without logging in with a local client. The Web client hasn’t gotten the same Yosemite facelift as the rest of OS X Server—it’s largely identical to the version that shipped with Mountain Lion and Mavericks. If you’ve used calendar software in the last few years, you won’t be surprised by any of OS X Server’s Calendar features.

Contacts

There’s very little to say about the Contacts service. It will sync contacts you create across multiple computers (making it potentially useful for families or other groups who want to maintain a shared list of contacts), and it will optionally display your Open Directory users when you perform searches in the Contacts app.

Messages

The Messages service enables a simpleExtensible Messaging and Presence Protocol (XMPP, or the protocol formerly known asJabber) server that allows your users to communicate with one another without using a third-party service like AIM or Google Talk. The service’s only options allow you to archive all chats (located on the server in /Library/Server/Messages/Data/message_archives) and enable something called “server-to-server federation,” which can both enable and restrict communication between user accounts stored in separate directories on different servers.

Many of OS X Server’s services are equally useful to OS X and iOS clients, but iOS lacks any sort of built-in chat client and so can’t take advantage of a local Messages server by default (despite including an app of the same name). It’s not difficult to find XMPP-enabled chat clients in the App Store if you want them, but you’ll have to navigate those waters on your own.

Connecting to your server

In OS X and iOS, the easiest way to get your clients connected to these services is to include them in configuration profiles you’re pushing out. If you’re not using Profile Manager (or if you have Windows, Linux, Android, or other clients), Apple’s use of well-supported protocols in all of these services means that you can connect manually from just about any client without much trouble.

To connect to your services in OS X, open up the Internet Accounts preference pane, scroll to the bottom, and click Add Other Account. Select “Add an OS X server account” and enter your server’s address if it doesn’t appear automatically in the list of nearby servers. Click Continue, enter your user credentials, and then select the services you’d like to use. Only Mountain Lion and Mavericks clients will support the syncing of Reminders and Notes, but older OS X clients can still connect to and use the older services.

To connect with other operating systems, you’ll just have to plug your server’s name and credentials into programs that support the protocols Apple is using: IMAP and SMTP for Mail, CalDAV for Calendar, CardDAV for Contacts, and XMPP/Jabber for Messages. The process is not as automated as in OS X, but it works.

NetInstall

The NetInstall service, known in older OS X Server versions as NetBoot, is aBOOTP-based system that allows Macs to boot from network volumes. This is usually done for the purposes of recovering files, running diagnostics, or installing clean or pre-configured OS X images on Macs.

Booting from a networked volume can be initiated either by holding the N key as your Mac starts up or by selecting a network volume in the Startup Disk preference pane. NetInstall forms the backbone of the Internet Recovery feature that lets newer Macs download a fresh copy of OS X from Apple’s servers; the difference is that with NetInstall you can serve up your own OS X bits locally. Apple provides tools for the creation of bootable images, though third parties likeDeployStudio also use the technology to simplify OS X imaging and deployment for larger numbers of computers.

Apple distinguishes between three different kinds of bootable volumes: first are NetBoot images, which allow computers to boot to a full OS X installation hosted on a server. To store user files, NetBoot images can use space on the local Mac’s hard drive, or they can be “diskless” images that store user data on the server and allow the built-in hard drive to be completely unmounted—useful for disk imaging and diagnostics. Second, there are NetInstall images, which are more or less network-hosted versions of OS X install media. Third, you have NetRestore images, which can dump a custom OS X image directly to a client Mac’s hard drive.

We need to attend to a couple of things before we can flip on the NetInstall service: first, choose which Ethernet port you’ll use to serve these images (Wi-Fi isn’t an option) and the volume you’ll use to store both the images themselves and any user data they generate. You’ll only really need to worry about the latter if you’re configuring diskless NetBoot images. If you store the images on the boot volume, which is the default setting, the NetInstall service creates a NetBootSP0 folder for images and a NetBootClients0 folder for user data in the /Library/NetBoot folder.

The last step is to give the service an image to work with—this is a job for the System Image Utility.

Creating a basic image with the System Image Utility

The System Image Utility is buried in Server.app’s Tools menu. By default, it gives you a simple menu that you can use to make NetBoot, NetInstall, and NetRestore images from either a bootable OS X volume (either on an external disk or a separate volume on the Mac’s hard drive; you cannot make an image of the currently booted volume) or a Yosemite installer located in the Applications volume (if your installer was deleted during an update from an older version of OS X, it can easily be re-downloaded from the Mac App Store again).

One of the System Image Utility’s limitations is that it can only create images of the currently running version of OS X—Yosemite’s System Image Utility can only make Yosemite images, Mavericks’ version can only make Mavericks images, and so on. This can make it a bit tedious to create images for multiple OS X versions if you need to support older Macs dropped by newer OS X releases or if you want to support installations of older versions of OS X for some specific reason.

Clicking the Customize button reveals an Automator-like workflow builder that you can use to customize your images with application install packages and local user accounts and to set model and/or MAC address-related restrictions on the Macs that can use the image you’re creating.

For our purposes, let’s just download the Yosemite installer from the Mac App Store and create a basic NetInstall image of it so that we can install the OS on our Macs without having to re-download the installer a bunch of times ortote around a USB drive. Once you download the Yosemite installer, start up the System Image Utility, select the Install OS X Yosemite entry from the Sources menu, select NetInstall, and click Continue. Name the image whatever you want and click Create. Agree to the license agreement and the System Image Utility will automatically dump a NetInstall image in our NetBootSP0 folder from earlier (or anywhere else you specify, if the computer you’re creating the image on won’t actually be serving it).

Configuring images for booting

Return to Server.app and double-click the newly created Mavericks image to configure it for distribution. Check the box under Availability and choose whether to distribute your images using the NFS or HTTP protocol. HTTP is the default, and you’re less likely to run into firewall problems if you stick with it.

After choosing a protocol, you can then set up MAC or model-based restrictions on individual images—this is in addition to the global access restrictions you can configure in the service’s Settings tab. Once you’ve configured your options and enabled an image, the service will turn itself on automatically, at which point your NetBoot images will be visible in the Startup Disk preference pane on other Macs on your network. You can host multiple images at once, but the image set as default will be the one your Macs try to boot from if you start them while holding down the N key.

Because NetInstall has been a feature on Macs for so long, you should be able to host images for and support PowerPC Macs alongside both newer Intel Macs and older ones dropped from the support list in Lion and Mountain Lion (Yosemite, happily,did not drop support for anything). Using properly configured filters, you can easily provide network booting for Macs going all the way back to the G3 iBooks and PowerBooks if you still have a need for those older machines in your home or business, and I used the NetInstall service extensively while I wasplaying with old Macs earlier this year.

Websites

The Websites service provides the backbone for several of the other services we’ve talked about: Profile Manager, the Web-based Calendar, and the Wiki service. The service’s backend is supplied by Apache 2.4.9, which isvery nearly the newest version—older OS X Server versions shipped with Apache 2.2. You can also run PHP (version 5.5.14, newest versions are 5.5.17 or 5.6.1) and Python (version 2.7.6, newest is 2.7.8 or 3.4.2) code on the server if you’ve enabled those features. If you need access to Apache’s directory structure, it’s located at/Library/Server/Web/Config/apache2.

Turning the Websites service on creates a default website, which you can see if you type localhost/default in your server’s browser. By default, it’s just a simple landing page with links to some of the different Websites-supported services (like the Xcode server and the Profile Manager), but you can drop different files into the /Library/Server/Web/Data/Sites/Default directory to change that up. Clicking the Edit pencil will allow you to change who can access the site, where its files are stored, and what domains, redirects, and aliases it uses.

You can create new sites by clicking the plus button and setting the domain name, access permissions, SSL certificate, and other settings, and you can configure as many sites on your server as you have storage space (and bandwidth) for. Configuring advanced settings requires going into the Apache configuration files, a process which is partially detailed in OS X Server’s Help files and also inApache’s own documentation for version 2.4.

There are two deterrents to using the Websites service to host anything other than the pages for Server’s other services: the first is that, as we saw above, Apple is using less-than-current versions of Apache, PHP, and other software packages, and by default you’re reliant on Apple to push out these updates whenever it feels they’re ready. The second is that updates for these packages are bundled with OS X point updates (and later, the security update roll-ups that are released periodically for older OS X versions). If these point updates fix critical problems with one service, but an included PHP update breaks a bunch of your code, there’s not an easy way to separate them from one another. It’s fine for a basic site and may even be usable as a testing server, but as usual, more advanced administrators will be left to look for a more powerful, customizable solution.

Wiki

The Wiki service goes hand in hand with the Websites service, both because Wiki depends on Websites to operate and because it’s the easiest way to get your users doing something useful with Websites. If you’ve got any experience with Wikis of any kind, the Wiki service doesn’t have many surprises in store for you—they’re simple websites that you can use to collaborate with other users, create and maintain posts, and upload and share documents and other files. If you used the Wiki service in Mavericks, it continues on without notable changes in Yosemite.

The Wiki service fills a role similar to Google Sites in the Google Apps suite, and it also has more than a little in common with Microsoft’s SharePoint (though that software is both more complex and more capable than what’s on display here). Using this Wiki software, you can edit and comment on pages, associate pages with other, related pages, see revision history, and get notified when documents or comments are added to a site. Users with access to the Wiki service can create as many Wikis or pages as they want, and user groups you create in Open Directory can be given their own Wikis to facilitate collaboration.

The built-in Wiki service is admittedly pretty simple, but if it isn’t to your liking, it’s easy enough to install something likeMediaWiki to your Websites server and use that instead. OS X Server already includes Apache and PHP, so you’ll just have to set up some database server software and you’ll be good to go.

VPN

The VPN service in Yosemite Server continues to support bothL2TP andPPTP VPN connections. All you need to do is select the protocols you want to support, your VPN server’s hostname (which is separate from your server’s regular hostname, a feature new to Mountain Lion), and your shared secret password.

If you’d like to provide VPN settings to clients without handing out information like the shared secret password, you can save a standalone .mobileconfig file right from the VPN service window to hand out (useful if you’re not already handing out these settings with the Profile Manager).

You can define the IP address range that VPN-connected clients will use—by default it uses 31 addresses in the high 200-range, so most home users won’t run into any trouble there—and set separate DNS settings for VPN-connected clients. You can define routes for your clients as well.

The VPN service is considerably easier to set up and configure than something like OpenVPN, and L2TP and PPTP are both widely supported protocols that can be used with most recent versions of Windows, OS X, Linux, iOS, Android, and Windows Phone with no issues. The biggest nit to pick here is that offering VPN services on an OS X server doesn’t provide any particular benefits for Macs and iOS devices. Microsoft introduced a feature calledDirectAccess in Windows 7 and Windows Server 2008 R2 that allows for seamless, always-on, VPN-like connections between servers and clients that make things a bit less messy for users who need to get on the corporate network from remote locations. While not a requirement for a decent VPN solution, it’s too bad that Apple hasn’t come up with its own attempt to “fix” the VPN problem.

If you do intend to run your own home VPN server (and there are definitely benefits, particularly if you find yourself working from cafes or other locations with unsecured Wi-Fi networks), there are some other concerns to keep in mind. If you have a standard home Internet connection, the odds are good that your IP address changes from time to time—not the IP address of your computer connected to your home router, but your external IP address that identifies your network to the rest of the world. You might consider a dynamic DNS service likeNoIP orDynDNS, which will track that IP address as it changes and make sure the right one is associated with your hostname. You might also look into abusiness-class Internet connection, which is usually more expensive than a home connection but generally comes with less restrictive terms-of-use, better support, and an option for a static IP address.

Finally, you’ll need to make sure to open the appropriate ports in your router’s firewall to make your server’s VPN service accessible from outside networks. Apple’s comprehensive list ofTCP and UDP ports used by OS X and OS X Server is helpful here. The VPN service typically uses UDP 500, UDP 1701, TCP 1723, and UDP 4500.

DHCP

OS X Server’s basic DHCP service probably won’t be useful to most home and small business users—your router is already handling this for you, and most individuals don’t need multiple subnets or anything like that. If you have lots of clients on your network, though, the DHCP service will give you more options than what is available in most home Wi-Fi routers.

As in Mavericks, the service allows you to configure multiple subnets on different physical network interfaces (orVLANs, for Macs with only one physical network interface), configure your DHCP ranges, set DHCP lease time, reserve specific IP addresses for specific clients, and view information on connected clients. Depending on your router’s firmware, you may actually have more network configuration options there than OS X gives you, but for homes or small businesses it’s nice to have all of these settings available in one simple tool, especially if you’re using it in conjunction with theDNS service and don’t want to have to jump around between different administration tools.

DNS

As DNS servers go, the one in OS X Server is pretty simple: you can specify forwarding servers to handle requests that your OS X server can’t handle (which can either provide redundancy or allow you to use OS X for some DNS requests but not others), decide the computers for which your server should perform lookups (for the server only, for clients on the local network, and for clients on other networks), and configure your host names, IP addresses, and aliases.

Click the Settings button and then click Show All Records, and you’ll be able to access more granular and advanced DNS settings. These includeprimary and secondary zones, a number of differenttypes of DNS resource records, and reverse DNS records. There aren’t many other frills, but it will get the job done.

Xsan

The Xsan Admin is a bit of a niche service in an operating system packed with niche services. It interfaces with Xsan 4.0 (up from 3.1 in Mavericks), a product that serves as Apple’sstorage area network (SAN) implementation. Part of the tool lives in Server.app, and the other part can be found in Server.app’s Tools menu; between the two of them, they allow you to manage bigFibre Channelstorage arrays.

Because setting Xsan up requires a Fibre Channel network, a couple of OS X Servers, and at least one networked storage array, we can’t give you much more information on the service’s operation than this. The Help files for Server.app and the Xsan Admin tool should be enough to get you started if this is something you’re interested in.

OS X Server is still kicking

OS X Server’s rate of improvement has slowed in recent years, though Apple is hardly ignoring it. It did get a full Yosemite-style visual overhaul, after all, which suggests that Apple cares about it enough to keep developing it in lockstep with the consumer version of OS X. The continuous addition of features and fixes over the course of the Mountain Lion and Mavericks releases of Server suggests that Yosemite Server will continue on in slow and gradual but still active development.

If we were going to worry about the state of the Mac server in 2014, our primary concern would actually be hardware. First they came for the Xserve, and I did not speak out, because Apple was clearly not going anywhere in Windows- and Linux-dominated enterprise-level server rooms. Then they came for theMac Pro Server, and I did not speak out, for thecheese-grater Mac Pros were far too expensive to be practical for the new home-and-small-business focus of latter-day OS X Server. Then they came forthe Mac Mini Server, and there was no one left to speak for it.

That is to say, any Mac can be a server, but no Mac is configured to be an especially good one anymore.

The 2014 Mini is still probably the best choice, and its lowered power usage is appealing, even if its lack of quad-core processors and mirrored storage options reduce its appeal compared to the purpose-built Mini Server. You’ll just need to live with the reduced processing power and be more careful about backing up to external drives (which, granted, are better supported by the new Mini’s twin Thunderbolt 2 ports).

When the Xserve died, the OS X Server software followed the hardware—it got cheaper and less powerful, but more focused and user-friendly. Yosemite Server is another good release in that vein, and there’s no reason for happy Mavericks Server users to stay away. It’s still a cheap and relatively easy way to offer basic network services to groups of Macs in homes and small businesses. If necessary, it can still be used alongside Windows and Active Directory to help manage groups of Macs in larger, mostly Windows-oriented IT shops. We just hope that the software doesn’t decide to follow Apple’s server hardware again and disappear.

Further reading:

Listing image: Aurich Lawson

Loading comments...

Loading comments...